In the USSR, after the end of the Great Patriotic War, new categories of citizens appeared:

- Heroes of the Soviet Union.

- Disabled people of the Second World War.

More than 90% of people who received awards during the Second World War became Heroes of the USSR . Their number amounted to more than 11,500 people , more than 3,000 of whom were awarded high rank after death. Just over 100 people were recognized as Heroes twice, out of 7 - after death. 90 women were awarded the high title, more than half of them were awarded posthumously. Special rights and benefits were immediately provided for these persons, information about this was posted in all public places.

Based on research data conducted in 2021, it is known that 1,800,000 WWII veterans and disabled people . A year earlier, their number was 2,130,000 . The number is decreasing inexorably.

WWII veterans

The state cares about its heroes; their work and role in achieving peace on Earth is difficult to overestimate. This category of citizens is entitled to many support options. The corresponding Federal Law No. 5-FZ “On Veterans” has been developed, in which you can learn about:

- The concept characterizing this status.

- Measures of social support for citizens.

- Persons who are entitled to financial payments.

- Objects where the law applies and how payments are organized.

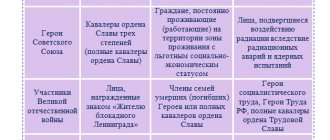

Based on the legislation, the category “WWII Veterans” includes:

- Persons who fought on the front line.

- Those who worked in the rear for six months or more.

- Awarded USSR medals for service and selfless labor.

- Persons whose work was related to air defense.

- Residents of besieged Leningrad who received a special medal.

- Soldiers who served in reconnaissance.

- Persons holding positions in internal affairs and state security bodies.

The term is broad and includes many categories.

What categories of citizens have the right to the status of a participant in the Second World War in Russia?

1. Veterans of the Great Patriotic War are persons who took part in military operations to defend the Fatherland or provide military units of the active army in combat areas; persons who served in military service or worked in the rear during the Great Patriotic War of 1941 - 1945 (hereinafter referred to as the period of the Great Patriotic War) for at least six months, excluding the period of work in the temporarily occupied territories of the USSR, or who were awarded orders or medals of the USSR for service and dedication labor during the Great Patriotic War. Veterans of the Great Patriotic War include: 1) participants of the Great Patriotic War: a) military personnel, including those transferred to the reserve (retired), who served in military service (including students of military units and cabin boys) or who were temporarily in military units, headquarters and institutions, those who were part of the active army during the civil war, the period of the Great Patriotic War or the period of other military operations to defend the Fatherland, as well as partisans and members of underground organizations that operated during the civil war or the period of the Great Patriotic War in the temporarily occupied territories of the USSR; b) military personnel, including those transferred to the reserve (retired), private and commanding personnel of internal affairs bodies and state security bodies who served in cities during the Great Patriotic War, participation in the defense of which is counted towards length of service for the assignment of pensions at preferential rates conditions established for military personnel of military units of the active army; c) civilian personnel of the army and navy, troops and internal affairs bodies, state security bodies, who held regular positions in military units, headquarters and institutions that were part of the active army during the Great Patriotic War, or who were in cities during the specified period, participation in the defense of which is counted towards length of service for the purpose of granting pensions on preferential terms established for military personnel of military units of the active army; d) intelligence and counterintelligence officers who performed special missions during the Great Patriotic War in military units that were part of the active army, behind enemy lines or on the territories of other states; e) employees of enterprises and military facilities, people's commissariats, departments, transferred during the Great Patriotic War to the position of persons in the ranks of the Red Army, and who performed tasks in the interests of the army and navy within the rear borders of active fronts or operational zones of active fleets, as well as employees of institutions and organizations (including institutions and organizations of culture and art), correspondents of central newspapers, magazines, TASS, Sovinformburo and radio, cameramen of the Central Studio of Documentary Films (newsreels), sent to the army during the Great Patriotic War; f) military personnel, including those transferred to the reserve (retired), private and commanding personnel of internal affairs bodies and state security agencies, soldiers and command staff of fighter battalions, platoons and people’s defense units who took part in combat operations to combat enemy landings and combat operations together with military units that were part of the active army during the Great Patriotic War, as well as those who took part in military operations to eliminate the nationalist underground in the territories of Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia in the period from January 1, 1944 to December 31, 1951. Persons who took part in combat trawling operations in units that were not part of the active fleet during the Great Patriotic War, as well as those who were involved by organizations of Osoaviakhim of the USSR and local authorities in demining territories and objects, collecting ammunition and military equipment in the period from 22 June 1941 to May 9, 1945; (as amended by Federal Law No. 426-FZ of December 22, 2021) g) persons who took part in hostilities against Nazi Germany and its allies as part of partisan detachments, underground groups, and other anti-fascist formations during the Great Patriotic War on the territories of other states ; h) military personnel, including those transferred to the reserve (retirement), who served in military units, institutions, military educational institutions that were not part of the active army, in the period from June 22, 1941 to September 3, 1945, at least six months; military personnel awarded orders or medals of the USSR for service during the specified period; i) persons awarded the medal “For the Defense of Leningrad”, disabled from childhood due to injury, concussion or injury associated with combat operations during the Great Patriotic War of 1941 - 1945; (paragraphs “i” as amended by Federal Law No. 36-FZ dated 05/09/2021) 2) persons who worked at air defense facilities, local air defense facilities, in the construction of defensive structures, naval bases, airfields and other military facilities in within the rear boundaries of active fronts, operational zones of active fleets, on front-line sections of railways and highways; crew members of transport fleet ships interned at the beginning of the Great Patriotic War in the ports of other states; 3) persons awarded the badge “Resident of besieged Leningrad”; (as amended by Federal Law No. 57-FZ dated 04.05.2021) 4) persons who worked in the rear during the period from June 22, 1941 to May 9, 1945 for at least six months, excluding the period of work in the temporarily occupied territories of the USSR; persons awarded orders or medals of the USSR for selfless labor during the Great Patriotic War. 2. The list of military units, headquarters and institutions that were part of the active army during the Great Patriotic War is determined by the Government of the Russian Federation. The list of cities, participation in the defense of which is counted towards length of service for the purpose of granting pensions on preferential terms established for military personnel of military units of the active army, is determined by the legislation of the Russian Federation.

We recommend reading: Vologda Region Rural Specialist Benefits

Thank you very much for your answer. But I heard that the Russian Federation equated all Russian citizens to participants of the Second World War born before September 10, 1945, and Ukraine gave this status only until 1933. Since 1933 to September 10, 1945 in Ukraine they gave the status “Children of War”. Please help me find data about this. Thank you very much.

WWII participants

Participants of the Second World War is a narrower and more specific concept. Includes those who directly fought and participated in battles. They also include those citizens who were part of the Red Army, but did not get to the front. Such situations occurred due to the need for personnel to produce the necessary wartime attributes:

- Technique.

- Equipment.

- Accessories.

- Weapon.

This category of citizens includes:

- Persons who served in the line of duty in the battles themselves and saw all the horrors of war with their own eyes.

- Military intelligence, internal affairs and state security agencies.

- Soldiers of the navy and ground forces.

- Persons who carried out mine clearance work.

- The soldiers who liberated Leningrad received a medal for defending this city from the German invaders.

- Persons recognized as disabled from childhood as a result of hostilities.

Participants also served in units that were not part of the active army for at least six months. That is, they could teach at military academies with a military rank. Participants also include military personnel who have been awarded awards for their service, as well as those who have become disabled.

What rights and benefits are entitled to WWII veterans in 2021?

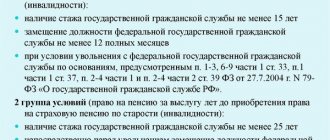

- Monthly payment of pensions and benefits, the amount of which varies depending on the category and merits of the participant in hostilities;

- Providing housing. The right is exercised once and does not depend on the property status of the participant in the war;

- Compensation of 50% of the cost of utilities. These include, but are not limited to:

- renting and maintaining a house;

- contributions for major repairs if the housing is located in an apartment building;

- provision of water, electricity, gas;

- wastewater disposal;

- fuel and its delivery, in the absence of central heating.

- Installation of a landline telephone without waiting in line;

- Advantage for joining cooperatives and other associations of citizens without a commercial component;

- Provision of free medical care, including in-depth examination at the dispensary (Order of the Ministry of Health No. 571). As well as maintaining the right to professional assistance in medical institutions where the veteran was observed before he retired;

- Free production of any types of prostheses and their installation, with the exception of dental prosthetics. As well as compensation for their cost in case of production at your own expense;

- Priority in using part or full annual paid leave and the right to use leave without pay for a duration of 35 days;

- Preferential service in communication institutions, the social sector, retail trade, the purchase of tickets to cultural and sporting events without queuing;

- Priority in admission to nursing homes, as well as assistance from social workers at home.

The amount of compensation, pension payments, benefits and other benefits depends on the category to which the veteran is classified. Legislatively, the list of benefits is determined by Articles 14-19 of the Federal Law “On Veterans”, and the amount of transfers is determined by Article 23.1.

- For war invalids - 5403.22 rubles;

- For participants who have become disabled - 5403.22 rubles;

- Ordinary participants of the Second World War - 4,052.40 rubles;

- For combat veterans and survivors of the siege - 2972.82 rubles;

- Citizens engaged in the construction of strategic structures, air defense maintenance, who served in military units that were not included in the active army - 1,622 rubles.

We recommend reading: Can Bailiffs Seize a Computer or Phone?

The indicated amounts include the price of a set of social services (NSS). If you wish to maintain the NSO, this amount is deducted from your monthly payments.

What is common between the concepts of a WWII veteran and a WWII participant?

In 1930, one of the first documents was published describing the rights of military personnel of the Soviet army. According to it, some privileges also extended to family members whose relatives were at the front. The document also spelled out who specifically was entitled to what benefits and rights. For two decades, these opportunities have been available to the military and mercenary soldiers serving in the army.

And by the 20th anniversary of Victory in the Great Patriotic War, the category of citizens entitled to benefits began to expand. At first this happened for disabled people and relatives of those killed in the war of 1941-1945. Further, persons who became disabled as a result of service while performing their official duties in defense of the Motherland received the right to benefits. home front workers who received special awards for their work were included in this category of beneficiaries As well as persons awarded for participation in the defense of 5 hero cities, the Caucasus and the Arctic. After - participants in military operations during the siege of Leningrad. At first, these included those awarded a special medal , then - workers during the blockade . Now this category of people includes everyone who is directly related to this difficult period and has been in the city for at least 4 months.

What the veteran and participant categories have in common is that all are directly related to combat . Only someone took part in them and belongs to the category of participant, and someone may not have participated specifically in battles, but worked in the occupied territory for a certain period of time and became a veteran in the general sense and on the basis of legislation. All veterans are participants in the Great Patriotic War, only the degree of participation is different.

Member or veteran

The documents confirming the status of a participant in the Great Patriotic War, the Ministry of Health and Social Development of the republic said, are both the certificate “Participant of the Great Patriotic War” and the certificate “Veteran of the Great Patriotic War” with a note on the right to benefits. The first is issued by the military registration and enlistment office, the second by the Department of Veterans Affairs of the Ministry of Health and Social Development. The concept of “veteran of the Great Patriotic War” is indeed broader than the concept of “participant of the Great Patriotic War”, since it includes, in addition to war participants: - persons who worked at air defense facilities, local air defense, in the construction of defensive structures, naval bases, airfields and other military facilities within the rear boundaries of active fronts, operational zones of active fleets, on front-line sections of railways and roads, as well as crew members of transport fleet ships interned at the beginning of the Great Patriotic War in the ports of other states; – awarded the badge “Resident of besieged Leningrad”; – citizens who worked in the rear during the period from June 22, 1941 to May 9, 1945 for at least six months, excluding the period of work in the temporarily occupied territories of the USSR; – awarded orders or medals of the USSR for selfless labor during the Great Patriotic War (hereinafter referred to as home front workers). All this is spelled out in Article 2 of the Federal Law “On Veterans”. For each category of veterans, separate measures of social support are established: for war veterans - Articles 15 and 17 of the above-mentioned Federal Law; those who worked at air defense facilities - Article 19, those awarded the badge “Resident of besieged Leningrad” - Article 18, home front workers - Article 20. All categories of these beneficiaries, as a rule, are issued a uniform document “Identification of a Veteran of the Great Patriotic War”. It indicates the article in accordance with which benefits are established for the citizen. From this mark you can find out what status of war veterans the beneficiary belongs to. In all likelihood, the minibus driver did not know these subtleties or did not bother to look at your document. I would like to ask the relevant services what is the difference between a participant and a veteran of the Great Patriotic War? Are these two concepts equivalent or not? The question arose in connection with a recent story. Once I got into minibus 331 and showed the driver my ID as a veteran of the Great Patriotic War. To which he answers me that only war participants are transported for free. I didn’t argue, saying, isn’t the veteran a participant, and got out of the car. At the same time, I felt as if I had gotten into someone’s pocket. Although in fact I am a participant in the war, I fought from 1943 to 1945. But this is not reflected in the certificate. Now everyone - both war participants, and persons equated to them, and even disabled people - have the same “Veteran of the Great Patriotic War” certificates. And if the fundamental difference between war participants and veterans is so important, maybe we should make different crusts?

Differences between a veteran and a participant in the Great Patriotic War

Over time, it became necessary to separate the concepts of participant, veteran and disabled person of the Great Patriotic War. Most people don't differentiate between these terms. In the 80s of the twentieth century, their numbers decreased noticeably; the state almost equated them all. Then there was the collapse of the USSR and already in the Russian Federation, the concept of WWII veteran began to include persons directly involved in the battles for the Motherland, residents of besieged Leningrad, persons who served in the ranks of the anti-aircraft forces, those who served and worked in the rear for more than six months, persons awarded special medals for labor during the Second World War. And also everyone who worked in the rear for more than six months, was a prisoner of a concentration camp, served in state security agencies, intelligence agencies, and was a member of partisan detachments. They are entitled to many benefits from the state as an attempt to compensate for the consequences of participation in that bloody war.

Participants are those citizens of the Soviet Union who participated in battles, conducted intelligence activities, served at sea or on land, and gave their duty to their homeland on the front line. Some of the people who were drafted into the Army, but did not go to the front, also belong to this category. Over the years, this difference loses its meaning, as the number of people who took part in the Second World War and became veterans becomes fewer and fewer. At the same time, there are differences and are even spelled out in Federal legislation.

All participants of the Second World War are veterans . But not every veteran was a participant in understanding his presence on the battlefield.

There are currently many fewer WWII participants left than veterans. As of 2021, there are 75,495 combat veterans and disabled people . The state takes care of these citizens, whose numbers are noticeably decreasing every year.

People and societyComment

The concept of a combat veteran and the procedure for assignment

- The status of combat veterans is assigned only to employees of military units, while participants are recognized as persons who served in the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Federal Penitentiary Service or civilians who participated in hostilities.

- Veterans were in hot spots for a long time, while participants were not for long, and were immediately recalled or removed from the danger zone.

- during the Great Patriotic War, including military personnel of the Soviet army, partisans, underground fighters, intelligence officers, counterintelligence officers and students of units and subunits;

- military personnel who were involved in identifying and eliminating underground nationalist groups in the Baltic states, Ukraine and Belarus;

- military personnel, as well as employees of internal affairs bodies and the Federal Penitentiary Service, who served in hot spots of the CIS at a time when armed conflicts took place there, on the territory of Tajikistan, Nagorno-Karabakh, Dagestan, Transnistria, and also participated in the Chechen War;

- military personnel involved in the delivery of goods and people by vehicles to Afghanistan during the presence of the Russian military contingent there;

- employees sent to hot spots by the Ministry of Defense;

- pilots who flew combat missions during the Afghan operation;

- civilians and civilians who found themselves in a combat zone and involved in military operations.

Please note => Preliminary agreement for the purchase and sale of an apartment with a mortgage

“They were gathering in a park near the station.

Some were missing an arm or leg, some (former pilots) had burn marks on their faces. They sat on benches and begged passengers for bread. When it got dark, the disabled would sometimes get into heated arguments and swear. The most “violent” ones were detained by the police, but then quickly released. Law enforcement officers tried not to mess with disabled people again,” says old-timer Andrei Arterchuk about the realities near the Shepetivka railway station 60–70 years ago.

We have a very little idea about the appearance of that category of people, whose representatives were so memorable for Andrei Moiseevich. After all, photographs with images of people crippled by the war were under an unspoken ban. They were not advertised either in the press or in books. On the instructions of the Deputy People's Commissar of State Security of the USSR Bogdan Kobulov, from the end of January 1945, censors of department “B” of the NKGB seized photographs of front-line soldiers with amputated limbs, blindness, and disfigured faces, even from letters of ordinary Soviet citizens. And then these “trophies” were hidden so “reliably” that they cannot be found even in the archives of modern intelligence services...

| Instruction to the NKGB censors on the need to remove from letters of Soviet citizens photographs showing war invalids with severe physical injuries (Industrial State Archive of the SBU, fund 9, file 223-sp). The document is published for the first time | |

As of February 1, 1946, up to half a million disabled people from the Soviet-German war lived in Ukraine. Of these, 7,941 people belonged to the first disability group, 189,560 to the second, and 264,954 to the third. Almost every tenth disabled front-line soldier (39,880 people) had an officer rank. Among the latter, there were 21,503 disabled people of the second group. This was followed by representatives of the third (16,539 people) and first (1,038) disability groups.

Russian artist Gennady Dobrov (1937–2011) created a series of drawings called “Autographs of War.” In the drawing “Rest on the Road” - soldier Alexey Kurganov, he lived in a boarding house in the Siberian village of Takmyk, Omsk region. He went through the war from Moscow to Hungary and lost his legs. Photo: gennady-dobrov.ru

Although Ukraine in those years was dominated by post-war devastation, the authorities practically did not worry about the life and health of disabled people. Measures to support them were taken, but often symbolic, half-hearted, and ineffective.

Firstly, they tried to provide housing for front-line soldiers without a fixed place of residence. However, there have been cases when some disabled people “idly” repeatedly petitioned the authorities for improved living conditions, since they were “not heard” there. For example, this is how Pavel Lebedev, a war veteran, member of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), and twice order bearer, searched for available “square meters.” Almost every day (after demobilization in October 1945) he visited the Chernivtsi city council and regional executive committee to ask officials to help his family of six people! - in search of housing. As a result, Lebedev was “lucky” - he received an apartment on December 15, when it was already frosty and snowing outside. The simple “apartments” that the city authorities provided him had no heating, no water, no electricity, not to mention furniture or utensils. Thus, the honored holder of the Orders of Lenin and the Red Banner had to sleep on the floor and cook food in canned food cans.

Since I don’t receive help, I live on 300 grams of bread

But disabled front-line soldier Merkotenko did not even receive such primitive housing. After demobilization, he eked out a miserable existence at the Znamenka station of the Odessa railway, namely, in a primitive shack on the site of his parents’ house burned by the Nazis. Since he quickly got tired of this “life”, he decided to complain to the Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Nikita Khrushchev:

“Sorry that I am writing to you and not to the local authorities. The fact is that she doesn’t perceive demands, requests, or even almost pleas... I’m not even nineteen yet, but I’ve already seen everything: the roar of guns, hunger, cold, and need with death. In 1943, not even seventeen years old, I became a soldier of the Red Army. Now my body is adorned with six wounds that I am proud of... Since December 1944, when I returned home from the hospital as an invalid, the long days of my need have dragged on. Our house is destroyed, and the hut that we built and live in “inclines” us to suicide. I wear old clothes from the hospital, my uniform is from the same place. I’ve been turning to the Znamensky authorities for ten months now and always hear the same thing: “no” or “if it happens, we’ll give it.” Since I don’t receive any help, I live on 300 grams of bread. I went to the city committee of the CP(b)U, and there the first secretary, Comrade Brazikevich, said: “We have nothing, you don’t have to go…”.

There are similar minor notes in a letter dated January 24, 1946 from front-line soldier Zelman Kvasha from Vinnitsa to his father in Cleveland, Ohio, USA:

“...My house burned down, everything was destroyed and destroyed. He was wounded twice; there is not a single finger on one of his hands. I can’t work; it’s only thanks to what my wife earns that I exist. We are naked and barefoot. Dear dad, I ask you, help me with at least something.”

“A story about medals. It was hell there." Ivan Zabara shows his medal “For the Defense of Stalingrad.” Bakhchisarai, 1975. Artist Gennady Dobrov. Photo: gennady-dobrov.ru

In the first post-war years, war veterans who were disfigured at the fronts did not receive a “disabled” pension. Even a penny allowance, which for some reason was called “rent”, could only be claimed by front-line soldiers with the first or second disability group. Representatives of the first category received 80–150 rubles a month from the state, the second received half this amount (in 1945–1948, the amount of rent constantly fluctuated). How meager these funds were becomes clear when comparing them with the prices of food and clothing. For example, in the summer of 1947, the market asked for 10 rubles per liter of milk, a kilo of pork cost 120, and a pound of rye – 850. An ordinary men’s suit in a “run-of-the-mill” general store cost an “exorbitant” 700-800 rubles.

In addition to the “fixed” amount, veterans crippled by the war were also given a “ration.” Disabled Pavel Kotelkov, who was detained by the OUN Security Service on suspicion of collaboration with the NKVD, claimed that his monthly ration included 9 kg of flour, 400 g of crackers, sugar, cow and vegetable oil, a liter of kerosene, 4 kg of salt and some that of American clothing. However, the size of these rations soon began to decrease. For example, in the summer of 1946, a native of the Volnovakha district of the Stalin region, Dmitry Levchenko, having a second group of disability, received only the so-called bread ration, and its amount was 50% less than before.

There’s not a log of firewood, and there’s nowhere to get it. According to the law, disabled people are given firewood, but it is 60 kilometers away, in the forest

Also, the state provided disabled people with a number of benefits, for example, priority for prosthetics of arms, legs, teeth, and was supposed to be provided with orthopedic shoes and corsets. Disabled people also received fuel for the winter. However, often much of the above was only declared on paper. For example, although according to official Ukrainian data in 1945, three factories and twenty-six prosthetic workshops produced as many as 23,504 prosthetic legs, 8,359 prosthetic arms, 13,649 pairs of orthopedic shoes and 794 corsets, letters from consumers of these products are littered with complaints about their quality. Many people only dreamed of a good prosthesis, unable to “get it” due to the shortage.

“The workshop, where experienced dental technicians Gavrilyuk, Barash and Katsman work, cannot serve disabled veterans of the Patriotic War, since it does not have the necessary materials - steel sleeves, steel castings, porcelain teeth, cement, etc. Dentures are made exclusively from customer materials,”

– the author of the article “Fair complaints of disabled people” wrote about post-war raw material problems in the newspaper “Kolkhoznaya Pravda” (published in the town of Slavuta, Kamenets-Podolsk region, issue dated June 30, 1946).

Although preferential provision of disabled people with fuel for the winter was declared in the second half of the 1940s, there was a catastrophic lack of transport to deliver it to their homes.

“There’s not a log of firewood, and there’s nowhere to get it. According to the law, disabled people are given firewood, but it is 60 kilometers away, in the forest. How and with what to take them out of there? Wherever I turn, you fly off like a pea from a wall. So we conquered the cold for the whole winter,”

– war veteran Fedko, a resident of Alexandria, Kirovograd region, complained to a relative. And out of 250 front-line soldiers with injuries who lived in Lutsk during the heating season of 1945–1946, only 78 people “got hold of” fuel. Of the 630 war invalids - residents of one of the central districts of Nikolaev - only 135 people kept warm in the winter with “Stalinist” firewood.

"The price of our happiness." Sergei Gerasimovich Balabanchikov. Klimovsk, Moscow region, 1978 Artist Gennady Dobrov. Photo: gennady-dobrov.ru

True, disabled people were exempted from paying tuition fees for themselves and their children. For the children of disabled officers, as well as those officers who died in the war, went missing or died from the consequences of wounds, education in 8–10 grades of schools, technical schools and universities did not cost a penny. This rule, by the way, began to apply at the end of 1944, when hostilities were taking place. For comparison, in the late 1940s, for one year of study at the Lviv Polytechnic Institute or University. Franko charged 300 rubles from “ordinary” students. Students of the Lviv Pedagogical College and the Railway Technical School paid twice as much - only 150 rubles - annually.

The above-mentioned benefits, of course, were not enough to live on for those disfigured at the fronts (and there were plenty of young people among them!). Therefore, they looked for opportunities to make at least some income.

“In the cities... from disabled people and the military in general you can get various goods looted in Europe (mainly from Germany),”

– OUNovets wrote in a review of events in the Zhytomyr, Kyiv and Kamenets-Podolsk regions over the summer and early autumn of 1945.

"Book about love." Polina Kirilova, a resident of a boarding school in the village of Nogliki in the north of Sakhalin Island. Sakhalin Island, 1976. Artist Gennady Dobrov. Photo: gennady-dobrov.ru

However, those disabled people who were engaged in selling things from the war times were “hunted” by the police. One day, at a market in Ivankov (now Borshchevsky district, Ternopil region), a policeman intended to detain one such merchant. But, as the document says, “a cloud of women” came running to help the disabled man. A general brawl began. “Did our husbands and children shed their blood at the front for you to trample on it now!? You, Stalinist thieves, will be destroyed by the Ukrainian partisans, like the Krauts!” shouted the traders. By the way, many disabled people also worked at the bazaar in Radomyshl, Zhitomir region. One day, a woman approached the table of a legless front-line soldier, mistakenly believing that he was selling butter. “Move away, I don’t have any butter,” the disabled man roughly pushed her away from the counter and hit her with a stick. Jumping to the side, the frightened woman began to curse the seller: “If only both of your legs were torn off in the war, and not just one!” He rushed after her, but due to his injury at the front, he could not overtake the woman.

On September 29, 1945, a resolution was issued by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine (Bolsheviks) and the Council of People's Commissars of the Ukrainian SSR “On employment and material and living support for disabled people of the Patriotic War.” The essence of the document is this. If you were a private in the war, be kind enough to get a job in a cooperative or artel and produce everyday goods. An officer? Such people were entitled to a more responsible position - head of a department at a factory, collective farm accountant, teacher, court employee. In less than six months after the “labor decree” was issued, more than 80% of the total number of disabled front-line soldiers who “settled” there after the war found work in Ukraine.

An example of the practical work of Soviet censorship in 1944. The document is published for the first time

But, unfortunately, having a job does not guarantee a decent life for disabled people. After all, many ordinary artel workers received very little. Due to low wages, for example, workers of the Krasnaya Zvezda sewing artel (in 1948 it operated in Zolochev in the Lviv region) stayed after the working day and sewed “to the left”, fulfilling private orders. Only the director of this artel, Pyotr Odintsov, earned more or less normal income—600 rubles a month—although this man, appointed to a leadership position “from above,” had absolutely no knowledge of either tailoring or shoemaking.

Deprived of adequate monetary compensation, disabled cooperators often produced low-quality products. For the same reason, they “turned a blind eye” to trends in customer demand and made virtually no changes to the product range. And they showed little interest in the quality of raw materials. And the prices for manufactured goods were unreasonably inflated, equating them to the cost of goods made from good quality materials.

On November 22, 1949, the Minister of State Security of the Ukrainian SSR Nikolai Kovalchuk summed up the results of the inspection of bases and warehouses of cooperative structures of disabled people, consumer and industrial cooperation, the Ministry of Local Industry and the Ministry of Trade. “Inspectors” found low-quality and defective goods (sewing products, knitwear, shoes, haberdashery, children's toys, food products, etc.) in the amount of 232,008,000 rubles!

For example, in the city of Stalino, on the basis of the artel named after. Osipenko found more than 5,200 women's shirts. The inspectors determined why they were lying around: the price per unit of goods (31 rubles) did not correspond to the quality of the raw materials (cheap scraps of fabric). For the same reason, men's suits, trousers, and women's skirts worth a total of 105,171 rubles were stored in the warehouse of the Luch clothing factory of the Kamenets-Podolsk regional industrial district. Buyers were also of little interest in the products of the “17 September” artel from the Drohobych region - incorrectly sewn shoes with curved heels, as well as defective candles with wicks that the “candle making masters” had incorrectly filled with paraffin.

4,756 pairs of unpaired shoes lay “dead weight” in the stalls and at the base of the “Pyatiletka” artel (Slavyansk, Stalin region). And in the warehouse of the Khimprom artel (Chernigov region) 35,000 boxes of substandard shoe polish have accumulated, as well as two tons of low-quality wheel ointment (used by owners of horse-drawn vehicles). The Metalist artel of the Dnepropetrovsk regional cooperative union experienced serious difficulties in selling toy children's guns (they accumulated for 186,200 rubles) and padlocks with a total value of 486,000 thousand.

"Old Warrior" Mikhail Semenovich Kazankov. Bakhchisarai, 1975. Artist Gennady Dobrov. Photo: gennady-dobrov.ru

Even being in such a difficult situation, disabled workers had to pay taxes, as well as fulfill a number of other “related” obligations to the state. As indicated in the report of the Zolochevsky district branch of the OUN for May 1947, Soviet disabled people of group II in the USSR were subject to taxes on land (cultivation of one hectare of land, including a 50 percent discount, “cost” 90 rubles per year), garden (annual tax calculated for one ar = 8 rubles), a cow (for one = 88 rubles), a horse (for one = 75 rubles), bees (1 hive = 4 rubles). The so-called grain supply was also charged to disabled people. In the first years after the war, they did not rent it out, but already in 1948 they began to do so.

The “norm” for a war-crippled farmer who cultivated a plot of land up to two hectares was three to four centners of grain per hectare per year. For example, from the 42-year-old resident of the Kitsmansky district of the Chernivtsi region, Nikolai Tkachuk, who returned from the front without both legs and fingers of his right hand, the state took 3 centners of bread per hectare. His fellow countryman Yuri Babchuk, without a right limb and with three young children “on his shoulders,” “filled the state bins” with a ton of grain from three hectares. Those peasants who ignored grain deliveries were dealt with by high-ranking “guests” from the region. In the house of one of the “debtors” - a legless invalid of the Great Patriotic War from the village of Stenka in the Zolochiv region - they described all the things, after which they “advised” the owner to “correct himself” in two days, otherwise they would go to court.

There are no prosthetics, but money must be handed over. It’s not my fault that you have to give something from your monthly payment to state needs, that’s the way we have laws and that’s the way it should be

Disabled people called the “voluntary-compulsory” purchase of government bonds a kind of “tax.” The villagers were persistently and systematically “pushed” to this by the same “guests from the region.” Exactly how, is evidenced by the dialogue in the village council of the village of Golgocha, Podgaetsk district, between local resident Osip Skripnik (who lost his leg near Berlin) and visiting agitator Shcherba. So, on July 1, 1948, the latter suggested that the disabled person spend part of his 70-ruble monthly income on government bonds. But he asked the agitator to help with the purchase of a scarce prosthesis. The “guest” angrily stated in response: “There are no dentures, but the money must be handed over. It’s not my fault that something needs to be given from the monthly payment for state needs, that’s the way we have laws and that’s the way it should be.” Outraged by what he heard, the disabled man began to shout: “Those who fought became cripples, I lost my leg near Berlin, and now we have to live in poverty? And you, those who have eaten your fill, are also beating people, saying that you stand up for them?” Hearing this, the official showed the front-line soldier to the door. But he didn’t leave the village council, so Shcherba grabbed the man and threw him out the door, finally hitting him with his boot.

In the spring of 1947, war invalid Gushkovaty from the Zaleshchitsky district was also “persuaded” to buy bonds, although his rent was half that of Skrypnyk. When the agitator, who was tired of waiting for the disabled person to decide, called him a “bandit,” he became angry: “I’ve been to America, Canada, Germany, but nowhere have I seen such a disaster as in the Soviet Union. Are you saying that we are all one homeland, brothers? Then why isn't it so? Because Vasily Mandryuk and Vasily Veselovsky - disabled people from the village of Petrivtsi, Melnytsia-Podilsky district, Ternopil region - did not sign up for large amounts of state loans, the first of them was kept in the basement by the representatives of the district committee of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) for one day, and the second - for three.

Give me a gun and I'll shoot myself, but I won't go to the collective farm

Although disabled people were actively “recruited” into collective farms, many flatly refused to join. For example, to such a proposal, war veteran Daniil Lutsiv from the Mykulynets district of the Ternopil region responded as follows on March 11, 1948: “Give me a gun and I’ll shoot myself, but I won’t go to the collective farm.” In the village of Strigantsy, Berezhansky district, agitators managed to “catch the demobilized Andrei Soroka on a collective farm hook.” The legless disabled person was convinced that he was signing a request for an increase in the disabled person's annuity, although in fact it was an application to join the collective farm. On the morning of February 20, 1948, shortly before the start of the collective farm meeting, “messengers” came to the disabled man’s house and warned him that he must come to the village council for a meeting. Realizing that he had been deceived, the disabled person began throwing indoor flowerpots and chicken eggs at the feet of the authorities, then stripped naked and announced his intention to go to the meeting in what his mother gave birth to. However, the visitors somehow managed to dress the “rebel” and “show him off” to the village council

A typical form for the quarterly report of the branches and military censorship points of the NKGB during the Soviet-German war of 1941-1945. The document is published for the first time

For those military personnel who have completely lost their ability to work, the Ukrainian SSR created a network of specialized boarding schools. Since such people often needed treatment, they were assigned to special “disabled” hospitals. As of March 23, 1946, there were 84 hospitals housing 20,250 war invalids.

"Unknown Soldier". Nobody knows anything about this man's life. As a result of severe wounds, he lost his arms and legs, lost his speech and hearing. The war left him only the ability to see. Psychiatric department of a boarding house on the island of Valaam, 1974. Artist Gennady Dobrov. Photo: gennady-dobrov.ru

Also in different Ukrainian regions there were 12 residential care homes for people with disabilities without a fixed place of residence. There, 544 war veterans found shelter over their heads. What was it like for front-line soldiers with injuries in these institutions? They, of course, did not enjoy life there. For example, the authorities forgot to provide the “inhabitants” of the Starobeshevo boarding school (Stalin region) with pillows; they slept on antediluvian straw mattresses. And the bed that was provided at the boarding school was declared “unsuitable for use” by inspectors. “Since cultural work in the institution is at a low level, hooliganism and stabbing are on the rise,” the MGB document reported about the life of Starobeshevo disabled people.

Having more than “plunged” into the problems of the post-war hard times, demobilized disabled people felt difficulties with social adaptation. Many of them actually had to start their lives over. Those who were unable to “get involved” in time gradually lost their human characteristics, degraded, and began to beg.

“Give me a ruble, because I lost my arm while swimming across the Dnieper, Oder and Vistula,” this is how disabled Easterners addressed passers-by on the streets of Lvov in October 1946. In the same month, in the Stanislavovsky district (now Ivano-Frankivsk region), the author of the OUN report reported,

“Disabled people from the Patriotic War, often with medals, walk around the city like ordinary beggars, rage, resolutely demand financial help from everyone they meet and their owners. At the same time they threaten.”

The notes of the OUN member about what he saw in the Dnieper region and Crimea, made by him several years later, have a similar content.

"Scorched by War." Front-line radio operator Yulia Stepanovna Emanova. Volgograd. 1975 Artist Gennady Dobrov. Photo: gennady-dobrov.ru

“Everywhere at stations in Ukraine I met disabled people from the so-called Patriotic War. They were often without an arm, a leg, or an eye, accompanied by guide boys. These disabled people begged for alms."

– notes the author of the document. Odessa, 1947.

“I came there - post-war times, full of disabled people...”,

– this is already a fragment from the memoirs of Irina Kozak.

At that time, the woman was the liaison officer of the commander of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, Roman Shukhevych. The cripples, “left behind after the war” and “wandering around the world,” amazed an eyewitness in June 1947 in the Vasilkovsky district of the Kyiv region. In the summer of 1948, four former front-line soldiers (two were missing one arm, the third was missing a leg, the fourth was missing both arms and legs) were begging for alms at the Satanovsky market in the Kamenets-Podolsk region. One of them turned to Andrei Zaverukha, who had come to do some shopping from the village of Tolstoy, with the following words: “Brother, don’t pass by, look at what I’ve gotten myself into.” And Maria Savchin, the wife of Vasily Galasy, a participant in the Ukrainian national liberation struggle, the leader of the underground Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists in Volyn, wrote about what she saw in Zaporozhye in 1954: “When we walked through the streets, we met beggars, often children, but mostly disabled people ( probably from the war).”

According to the Minister of State Security of the Ukrainian SSR Nikolai Kovalchuk, which he cited in a letter to the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine (Bolsheviks) Leonid Melnikov on April 7, 1952, police officers in the second half of 1951 and the first quarter of 1952 detained 8949 people “begging and vagrancy” element", including 2868 in Kyiv. Of these, 716 people were employed, 1,294 were placed in homes for the disabled and elderly, and 2,442 people were transferred to guardians. The remaining 4,498 people signed a subscription to stop begging.

A page from one of the reports on the facts of anti-Soviet manifestations and characteristic negative expressions among those demobilized from the Soviet army and disabled veterans of the Patriotic War. The bottom paragraph is the complaint of Nikolai Miruni, a disabled person from the Soviet-German war, a resident of the Vinnitsa region, about his hard life in 1946. The document is published for the first time

The number of those who, having a means of subsistence, wandered and collected alms for their own enrichment is impressive. For example, war invalid Kachanov regularly begged for coins from Kiev residents in the early 1950s, although he worked in the artel named after. Kirov for a good 500 rubles a month, and also received 125 rubles in rent. His “colleague” Naborshchikov, having his own house in Fastov, “travelled” around the capital’s trams and trolleybuses, pretending to be a former tanker who took part in the battles of Stalingrad and Odessa. In fact, he did not take part in hostilities, but received a concussion as a result of an accident while driving a car while drunk. Citizen Dolgin, having been demobilized from the front without two legs, collected sixty rubles a day, begging along the streets of Odessa, Lvov and Kyiv, and then drank everything he begged for. As an eyewitness testified, many “invalids of the Patriotic War” wandered in Lviv at the turn of 1949-1950. These people “earned” their living by stealing, robbing, or begging. Those of them who could not find a piece of bread (very often disabled people without legs, arms or eyes) staged fights, during which their accomplices “worked” the audience in the right direction.

"Russian prophet". Vanechka, a disabled beggar. The village of Tara, Omsk region, 1975. Artist Gennady Dobrov. Photo: gennady-dobrov.ru

By the way, the Kyiv police several times in a row failed to place the blind front-line soldier Semchenko in a boarding school, since he constantly categorically refused such a prospect, lived wherever he pleased, wandering the streets and singing plaintive songs to the accompaniment of a harmonica.

Cases of begging among disabled people increased significantly during the famine years of 1946–1947. Due to difficulties with food in eastern and southern Ukraine, many people, including disabled front-line soldiers, began to travel from there to Western Ukrainian lands for food. These “bag men” were often removed from trains, but they continued to get “to Zapadnaya” on foot, dragging a stroller with a bag behind them on a rope.

The political referent of the Bandera wing of the OUN, Yakov Busol, outlined in a letter to Vasily Kuk an interesting dialogue between a war invalid and NKVD workers, heard in the Rivne region:

A “disabled lieutenant of the Patriotic War” came to Verbshchyna for food, went into the village - and there the NKVD detained him and sent him back. He swears: “Are you looking for a bander here? Look for them in the Chernihiv and Kursk regions, because there are already local Banderas there too.”

And in the Zolochevsky district in March 1947, there were so many “bag men” that, as an eyewitness wrote, because of them “the houses simply weren’t closed.” The local residents called these visitors “proshaks.” Demobilized disabled Red Army soldiers without arms and legs, on crutches, “begged for bread with tears in their eyes.” Sometimes they offered something from scarce manufactures in exchange. According to information from the OUN member (June 1946), all freight trains were crowded with “proshaks.” Some not only walked around the villages and asked the villagers for alms, but also “brazenly stole everything they could get their hands on.”

"Defender of Nevskaya Dubrovka." Infantryman Ambarov Alexander Vasilyevich, twice covered with earth after fascist plane raids on Nevskaya Dubrovka. Valaam Island, 1974. Artist Gennady Dobrov. Photo: gennady-dobrov.ru

One day in the late autumn of 1946, after one of these “visits” to Western Ukraine, a disabled Soviet war sergeant was boarding a train in the opposite direction at the Stanislavovsky station. But his luggage (bundles of food) was so large and heavy that his fellow NKVD member became embittered and threw it off the train. The sergeant shouted: “I fought for the Soviet homeland, and now they are taking away my bread!” To which another fellow traveler, a foreman of the Red Army, objected: “Listen, guy, no matter what army you fight in, white or red, you and we still have the same turn. If you fought, you were given food; if you don’t fight, you don’t need to eat. Get out of here, otherwise you’ll go to jail.”

By the way, in many cases it was not limited to begging or bag-bags. After all, people with disabilities did not hesitate to speak out about the state of affairs in the country, they criticized the party, the government, and local authorities. Because they allowed themselves to voice their “uncombed thoughts,” they often became the object of surveillance by intelligence officers. In their “top secret” memos, they recorded the moods of disabled people with careful accuracy. Thus, on August 9, 1947, the Minister of State Security, Lieutenant General Sergei Savchenko, addressed all heads of regional departments with the following request in a “note on HF”:

“Until August 18 this year. g. send to the 5th Directorate of the Ministry of State Security of the Ukrainian SSR (engaged in political repressions. - Authors) a detailed report on the facts of anti-Soviet manifestations and characteristic negative statements among those demobilized from the Soviet army and disabled veterans of the Patriotic War.”

By the way, members of the OUN did similar things, but with a different goal - to search for “compromising evidence” on Soviet realities.

“On a bench near the Ternopil station sat a drunken invalid, an Easterner without both legs, and spoke about Stalin, the party and the government whatever he wanted. A policeman approached him and asked to show his documents. “Here is my document,” he pointed to the crutch. When the policeman tried to take the disabled man to the police station, he hit him on the head with a stick. ...He grabbed the railing of the bench with his hands and began to shout: “Give me the leg that the state took away from me, go to the front to show your strength, not here. Bring me the crutch yourself!”

This story is from the post-war OUN document “Vіsti about SUZ”. And the following data is already from the KGB. Agents “Mikhailov” and “Vladimirov” notified the NKGB of the Ukrainian SSR about “the presence at the Lvov State University of an anti-Soviet group of students from among the disabled of the Patriotic War who intend to discredit the party’s policy on the national issue.” And disabled Alexey Maleev was arrested only because on August 7, 1945, he sent an anonymous letter to the editor of the newspaper Pravda with “slander against the party and its leaders.” During the investigation, he confirmed that he wrote this letter because of disagreement with the activities carried out by the party and the government.

False stamp of the Soviet field mail from the war of 1941–1945. Photo published for the first time

Thus, the relationship between disabled front-line soldiers and the Soviet government was very difficult. In addition, the latter, already in peacetime, managed to use the sentiments of some cripples in its Jesuit combinations designed to discredit Ukrainian nationalists. After all, the attitude towards the Banderaites of such citizens as, for example, three-time fugitive from mobilization in the UPA, disabled person of the Great Patriotic War, three-time order bearer, senior sergeant Dmitrenko, could be easily predicted. Moreover, in September 1945, nationalists burned his house in the Solotvinsky district (Transcarpathia).

However, when reading such things, one should not forget that the security officers repeatedly sent legendary detachments of pseudo-rebels to Western Ukraine, who acted under the guise of the UPA. Here, for example, is an incident that occurred on June 4, 1946 in the village of Komarov, Galician region (now Ivano-Frankivsk region):

“A department of Bolsheviks came, dressed as UPA riflemen: in Mazepinka boots, embroidered shirts. They asked for bread and eggs and said that they had been walking through the forests for three years now. ...Calling themselves UPA shooters, they took away our clothes. A disabled war veteran, a Red Army soldier who returned from the second war without an arm, had his boots taken off his feet and beaten with beech trees, saying: “You bastard, you fought for Stalin, but you don’t want to help us.”

The next day, the victim went to the regional center and complained to the prosecutor about the arbitrariness. After that, they returned his boots, warning him not to tell anyone about what had happened.

Such “werewolves”, which were inherited from the Stanislavov region, were trained in the capital of Ukraine. As Ivan Bezkorovayny clarified during interrogation at the OUN Security Council (August 1947), personnel were selected from demobilized Red Army soldiers. They were taught the ability to pretend to be deaf and mute, to transform into disabled people or beggars who could walk around villages and overhear what people were saying about nationalists, collective farms, and the possibility of starting a new world war. Knowing this, the Central Line of the OUN ordered to treat Soviet disabled front-line soldiers with respect.

“Our national duty is a warm, cordial meeting of brothers, to whom we must openly explain with fraternal help how, following our example, they should fight the Soviet regime and its agents,”

– we read in an address to the peasants of Western Ukrainian regions in 1946.