Migrants instead of Russians: Who will be forced to change schools

President Vladimir Putin at a meeting of the Council on Interethnic Relations said that in Russian schools the percentage of migrant children should be such that they can be adapted to the linguistic and cultural environment. That is, in such a way that they adapt themselves, and do not begin to “adapt” our children to suit themselves.

Otherwise, the president warned, the situation will eventually be like “in some European countries, and even in the States, when the level of migrant children in school reaches a certain percentage, local residents take their children out of these schools...”

I confirm: this problem really exists. Moreover, on a scale significantly larger than those that are apparently reported to the president. When my grandson entered the preparatory class of an ordinary Moscow school in a residential area, it turned out that besides him, there were only three Russian children there. Of the rest, not all were from Central Asia, but there were also some from the Caucasus who practically did not know the Russian language.

At whose expense is the banquet?

Minister of Education Sergei Kravtsov, in response to the president’s words, said that his department is preparing a system for assessing the individual educational needs of this particular group of students, which will “identify the child’s level of language proficiency and possible problems in mastering the general education program” and set “the necessary educational trajectory and program psychological and pedagogical support" for schoolchildren. Plus, they will introduce special courses for teachers so that they “know the subtleties and know how to work with such children.”

It sounds very nice, but our minister immediately wants to ask: “At whose expense is the banquet?” After all, developing programs taking into account national specifics, creating special classes, training and retraining teachers - all this costs a lot of money! And according to the already established tradition, they will take this considerable money from our pockets. Instead of spending it on the education of our children, with which there are already a lot of problems in the country.

At the same time, for some reason, comrades who are concerned about the rights of migrants do not have a reasonable question: why on earth is Russia obligated to give these children an education?! After all, even if we agree with the delusional statement that we can’t live without migrants, it doesn’t matter – we invited workers of certain (as a rule, not requiring special qualifications) specialties to the country.

But not their numerous relatives, who arrive to us with a whole bunch of various diseases, with which, if they worsen, the ambulance will take them to the hospital, and there, willy-nilly, the “guest” will be treated for free. Not their wives and sisters in the last month of pregnancy, who come to Russia to give birth for free, because the Russians really won’t abandon a woman giving birth! Not their numerous offspring, whom we will teach at school for free, including the Russian language.

Representatives of a number of diasporas, having heard Minister Kravtsov’s promise to introduce a separate program for migrant children, immediately became indignant: they say that this will lead to the fact that migrant children, after the correction of educational policy, will find themselves in isolation. But I am much more worried that, finding themselves in a class where the majority will be the children of migrants, our own children will find themselves under such cultural, psychological and physical pressure that the only option for parents will be to change schools. In Europe, as the president rightly noted, there are already plenty of such cases: they are reaping the fruits of the “tolerant” madness that has gripped the West with might and main. And we have heard more than once that even teachers advise Russian parents not to send their children to what is practically a “migrant” school.

Migrantophilia at someone else's expense

As one 19th-century English author said, “I love my wife more than my cousin, and my cousin more than my neighbor. But just because I love my wife, it does not at all follow that I hate my neighbor.” So I, a sinner, treat everyone who comes to us without any hostility. But at the same time, I still love my compatriots more.

Therefore, I am convinced that the state has the right to provide some benefits to migrants and their families only if its own citizens are already fully provided with the same benefits. And I am sure that Uzbeks in Uzbekistan, Tajiks in Tajikistan, etc. will approach this issue in exactly the same way. Because this is the only correct and logical approach that sets priorities in distribution, where any lamentations about “equality of opportunity” are from the realm of liberal nonsense.

What Lomonosov said, “If in one place as much is taken away, the same amount will be added in another,” it seems that no one has yet canceled it. This means that any humanitarian gifts to migrants and their families are made at our expense. In a country where there are, to put it mildly, very significant problems with the social security and financial situation of citizens, such “charity” of the state is perceived as almost a betrayal of its own citizens. Because what is given to migrants and their families will have to be torn away from us and from our children.

Yes, in Russia there is a law that all children (including children of non-citizens) not only can, but are obliged to receive free secondary education. To visit kindergartens, in which there are always not enough places for ours - by the way, too. It's like that. Just explain to me why on earth all this is my and your problem? And why should you and I have to pay for all this, and besides, endure a lot of inconvenience from it?

The children of our deputies who pass such “humane” laws and say beautiful words about “migrants also have rights”, as a rule, study in completely different (privileged, or even foreign) schools, where there is no problem of joint education with people from other cultures and non-speaking in Russian by peers. They can afford to be treated in paid clinics, not knowing that even in Moscow, in “free” clinics, you have to wait in line to see another specialist two or three weeks in advance, or even earlier. In general, one might say, they live on another planet, increasingly perceiving their kind Fatherland as something like a village with serfs, where the master only occasionally visits from Paris to collect his quitrent.

We are left alone with the “migrant” problem. At the same time, even migrants who are more or less hooked in Moscow give birth to several similar children within a few years, because if the father of the family stays in Moscow for a certain time, he will receive citizenship. And along with him - the entire “village” he brought. And then other relatives will join in – on the subject of “family reunification.” They are “tolerantly” silent about this, but the ethnic composition of our cities (especially capital cities) is changing at a very rapid pace. Before we know it, people in Moscow stores will no longer understand Russian.

Is there a way out?

The solution is still the same: the state is primarily obliged to attract to work not those who are “more in number, cheaper in price,” but people of the same culture and language as us, who at least do not need to be “adapted.” First of all, of course, Russians (Great Russians, Little Russians and Belarusians). But also Russians by cultural affiliation, who speak and (preferably) think in Russian.

In our emergency room, for example, there is a doctor who works - a good, attentive guy, whose nationality is either Kyrgyz or Kazakh. Speaks Russian perfectly without an accent. Both his family and children, I am sure, also speak excellent Russian and have no problems adapting to school. And they don’t create problems for us either.

And I also immediately become attracted to young non-Russian mothers on the street if they communicate with each other and with their children in Russian. For this means that normal cultural assimilation is taking place in the family, and their children, when they grow up, will consider themselves not a foreign diaspora in a foreign Russia, but an integral part of our country.

But in order for precisely such approaches to set the tone in the migrant environment, the state must promote them. Which, unfortunately, is not the case yet. We do not shape the migrant environment in the way we (citizens) need, but allow it to shape the reality around us in its own image and likeness, paying for this, moreover, from our pocket.

And all this happens because the tone in state national policy is set, alas, by the interests of businesses parasitizing on migrant labor and various officials who cling to migrants like leeches. The interests of the state and (first of all) its citizens must be asked. That is, you and me. If not, then this is not an “international” policy, but the most “anti-national” policy.

But the president said the right words. Perhaps at least something will now move in the right direction. After all, in our God-saved country, until the president (tsar, secretary general) expresses his opinion, not a single government official will do anything worthwhile for the country - that’s how they were raised...

Quotas in schools for children of migrant workers will be introduced in person

The authorities decided to recognize the ethnic diversity of the Russian school as a social problem. Photo by RIA Novosti

The Kremlin’s website does not yet contain the president’s instructions following the meeting of the Council on Interethnic Relations on March 30. Then Vladimir Putin suggested thinking about quotas in school classes for migrant children to make it easier for them to adapt. As NG found out, this did not seem to be impromptu. Since April, updated school admission rules have been in effect, which, according to experts, complicate life for visitors. For example, you will have to prove the legality of the child’s migration status. This is already a departure from the principle of “education for all,” but in the regions that are most attractive to migrant workers, schools are indeed beginning to turn into migrant schools, and the indigenous residents are outraged and take their children away. That is, what Putin warned against at the Council meeting is happening. It would be more logical for the authorities to build more schools, but in the pre-election period the priority is on quick solutions - not so much effective as informationally attractive.

Putin set officials the task of optimizing the quantitative presence of migrant children at school. His statements at a meeting of the Council on Interethnic Relations, as it now becomes clear, only looked like some kind of reflection, but most likely it was conveying information about decisions already made. Perhaps this is why the list of the president’s instructions on the problems that were discussed on March 30 has not yet appeared - there is simply nothing to add to it.

According to Putin, “in some European countries, and even in the States, when the level of migrant children in school reaches a certain percentage, local residents take their children out of these schools... Schools are formed there that are actually 100% staffed by migrant children. In Russia, under no circumstances should events of this kind be allowed to develop.” This was the presidential commentary on the report of the head of the Ministry of Education, Sergei Kravtsov, who called the work of adapting immigrant children one of the key tasks of the department. One of the areas of such work was called Russia’s manifestation of its “soft power” in the form of the construction of new Russian schools in those CIS countries where the main migrant flows come from. It is unclear, however, why the Ministry of Education did not declare it a priority to increase the number of school places, at least in the regions most popular among guest workers, since only certain constituent entities of the Russian Federation can afford to build new schools in the required number.

As it turned out, this department simply initially decided to take a different path - and human rights activists are already criticizing the updated rules for admission to Russian schools. A considerable part of them is dedicated specifically to migrant children, whose right to education, experts believe, is now made dependent on their migration status. This calls into question the basic principle that everyone has the right to receive knowledge. The fact is that in April a revised procedure for submitting applications to schools came into effect. The Ministry of Education assured that the innovations “will facilitate the enrollment process, make it as comfortable as possible and help get rid of queues.” However, all this will not be for visitors, who are made clear that the right to education is made dependent on registration. For example, a rule is being introduced to verify the legal grounds for the presence of a particular child in the Russian Federation, which, in fact, according to NG experts, contradicts not only international, but also domestic legislation. Moreover, from the document we can conclude that the school administrations themselves will check the registration of children in the Ministry of Internal Affairs databases and decide who is legally staying in Russia and who is not, that is, they can study here or not.

There are now almost 800 thousand migrant children in the country, of which about 140 thousand (17.5%) are in the Russian school system. Some regions, which account for their largest shares, are already scratching their heads over how they will inspect schools and weed out excess foreign children. But the innovations of the Ministry of Education come in handy - already this year quotas can actually be introduced in person. “The new procedure for admission to schools is nothing more than a bureaucratic filter in order to prevent migrant children from entering schools,” Alexander Brod, a member of the Presidential Council for Human Rights, confirmed to NG. This document, according to him, runs counter to the State National Policy Strategy, the Concept of Migration Policy, and the recommendations of the Federal Agency for Nationalities on the sociocultural adaptation of visitors.

The only message from such documents, Brod said, is not to let them go: “Let migrant workers go, be useful, and the country will spit them out like waste slag. This demonstrates the triumph of bureaucratic squalor, conservatism and, to a greater extent, satisfies the cavernous interests of chauvinists rather than consistent with humanistic legal norms and the country’s real needs for workers.” If a person comes with his family, the human rights activist noted, this indicates his serious intention to take root on Russian soil. And the new procedure for admission to schools only “frees hands for persecution of migrants and even for ethnic cleansing, as well as for corruption schemes.” “In a word, this is the bleeding of the country, depriving it of new workers, which means it is damage to the economy and a blow to the well-being of Russians. It’s amazing how this order was accepted, because it only creates disorder,” Brod emphasized.

The extremely low quality of legal creativity of the Ministry of Education was also noted in the study of the analyst of the “Civic Assistance” committee (recognized in the Russian Federation as an NGO-foreign agent) Konstantin Troitsky. There is only one positive change in the new rules - priority is given to the admission of children to those schools where their brothers or sisters study. But there are three clear deteriorations that “could undermine access to schooling for many children across the country.” For example, in an application for admission to a school, parents are required to indicate the address of their place of residence and (or) stay. It seems like nothing special, and the word “registration” doesn’t sound right, but the new wording is precisely related to migration legislation.

Schools will also be required to check the accuracy of the information specified in the application “and the validity of the submitted electronic documents.” Therefore, it will be necessary to request information from law enforcement agencies. Among other things, migrants will have to prove the child’s right to stay in the Russian Federation, that is, families will have to obtain a certain document in this regard. “The Ministry of Education requires proof of the legality of the stay of children without Russian citizenship in our country. Although neither the competence nor the powers of the educational authorities include the implementation of migration control and determination of migration status,” Troitsky asserts. By the way, there is not yet an exhaustive list of documents that could prove this right, which means that “the norm can lead to a number of absurd incidents when, for example, a parent – a Russian citizen – has a child who is a foreign citizen, and that child’s expiration date has expired.” , for example, the visa period.”

Education for foreigners in Russia

Recently, the flow of migrants to Russia continues to increase, and therefore the Russian government provides for the availability of education, including for foreign citizens. Migrants have the right to enroll in schools, colleges, and universities on the same basis as Russian citizens. There are also educational institutions that position themselves as institutions for training foreigners (for example, RUDN University). At the same time, language training courses are organized for foreign applicants, study quotas are provided, and grants and scholarships are allocated. Citizens of the CIS are especially welcome in our country in accordance with signed international agreements. The best students, based on a quota, have the right to receive free education in Russia.

The situation and rights of migrants in the field of school education in Russia

In the article, the author examines the legal status of migrants in the field of school education and proposes integration mechanisms.

Key words: migration, migrants, schools, school education, migrants' rights.

Regulatory support in the field of migration policy in Russia includes [48]:

− federal and regional legislation;

− by-laws to specify the norms of legislation of indirect effect, approved by resolutions of the Government of the Russian Federation;

− decrees of the President of the Russian Federation;

− international bilateral and multilateral treaties and agreements regulating relations between states in relation to external migration.

The internal legislation of the state, when implementing migration policy, must strictly comply with the norms of generally recognized international law. Russia officially joined them, taking upon itself obligations to implement them.

As practice shows, if issues of determining the legal status of foreign citizens are within the competence of the state, then integration issues, issues of adaptation and provision of first aid to migrants are resolved largely with the active participation of non-governmental organizations. State power, within the framework of the dialogue between government and civil society, is represented by institutions that are authorized to manage in the field of national national policy and migration policy, including federal executive authorities, in particular, the Federal Agency for National Affairs, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and other departments and ministries.

In Moscow, children of migrants usually study in non-prestigious schools. It depends on the financial capabilities of the parents. Other reasons are the level of education and preparedness of children when they enter school. Muscovites' children study in prestigious gymnasiums and lyceums. Therefore, a number of schools with the largest number of immigrant children are now called “migrant schools.”

There are other reasons that become an obstacle to migrant children receiving a full-fledged education in Russia. These are barriers to collecting the documents required in Moscow for a child to enroll in school. Parents must join the electronic queue on the website of the Ministry of Education of the Russian Federation and provide some additional documents, for example, a certificate of migration registration. Internal migrants, Russians, also face these problems.

It is noted that the legal framework of the Russian Federation provides rights to education to foreign citizens. In particular, legislation in Russia provides equal rights for everyone. “Foreign citizens and stateless persons have the right to receive education in the Russian Federation in accordance with international treaties of the Russian Federation and this Federal Law. Foreign citizens have equal rights with citizens of the Russian Federation to receive preschool, primary general, basic general and secondary general education, as well as vocational training programs for vocational training in blue-collar professions, office positions within the framework of mastering the educational program of secondary general education on a publicly accessible and free basis "[6].

Another aspect concerns the fact that the Concept of State Migration Policy until 2025 identified the main and priority tasks of the activities of public authorities for the adaptation and integration of foreign migrants in the Russian Federation. The key elements of state migration policy are the creation of appropriate conditions “for the implementation of adaptation and integration of migrants, the implementation of the protection of the rights of migrants and their freedoms, as well as ensuring their social security” [48].

In accordance with paragraph 3 of Art. 62 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation, foreign citizens and stateless persons are endowed with rights and responsibilities in the Russian Federation on an equal basis with citizens of Russia” [4]. The Federal Law “On Education in the Russian Federation” states that “the principles of state policy are to “ensure the right of every person to education, the inadmissibility of discrimination in the field of education” [6].

In 2015, in the city of Moscow, enrollment in educational institutions is carried out via the Internet, namely through the Portal of State Online Services of the City of Moscow, which became the only way to submit an application for a child to enroll in school. The application form is designed in such a way that the child’s parents cannot submit it without indicating the registration address. Moreover, in the subsection “Enrollment in 1st grade” in the paragraph “Who can apply for the service” it is stated that these are “parents (legal representatives), whose children: are registered by the registration authorities at the place of residence in the city of Moscow”, and also “registered by the registration authorities at the place of residence in the city of Moscow.”

So, at the moment and today, a foreign citizen without registration cannot enroll his child in Moscow schools. "This applies to:

a) asylum seekers,

b) people who have received refugee status or temporary asylum in Russia, but are not able to register themselves,

c) foreign citizens who appeal the refusal to grant asylum,

d) as well as all undocumented migrants” [6].

In some cases, directors, when placing a child in schools, require parents to register for a year, not agreeing to accept a three-month registration, which is done by foreign citizens entering Russia on a visa-free basis. Thus, parents of children who are foreign citizens, when enrolling their child in school, are required to have a document “confirming the applicant’s right to stay in the Russian Federation.” This rule does not allow migrants in Russia to enroll their children in school. This also applies to foreign citizens seeking asylum in Russia, but who have not yet received it or are at the stage of appealing the refusal. The appeal process often takes up to a year. And then the children of migrants do not attend school.

A separate problem is the use of educational institutions to identify undocumented migrants. This problem is particularly acute in Moscow and St. Petersburg, and is also evident in other regions. For example, the Civic Assistance Committee has been working with the Syrian refugee community in the city of Noginsk, Moscow Region, since 2014. The head of the education department of this city, Natalya Sergeevna Asoskova, took an extremely tough position on the issue of access of foreign children to schools in the territory under her jurisdiction. And such gaps have not yet been completely eliminated; the process of resolving them has been delayed. Close cooperation between education authorities and migration control agencies is often not hidden.

Migration processes are marked by new trends. Now families are coming to Russia. The new phenomenon of family migration prompts solutions to new problems at the legislative level. For example, these are the legal conditions for the stay of visiting families in the country and their children.

“The rights of children are an inalienable and unconditional attribute, and the situation of foreign children temporarily staying in the country requires legislative support” [49].

Despite the seemingly legislative norms regarding the education of migrant children in the Russian Federation, it can be said that there are some contradictions in the area of problems in school admission.

In particular, we are talking about the fact that if there is an attitude towards universal education of all children, there are frequent cases when parents are refused to enroll their children in school; as a rule, it is allowed, by the predominant professional desire of school directors, to cover all children living in the area of location with education schools.

First of all, it is worth noting that in order to find out in time what problems children have, it is necessary to systematically study this area. By carrying out this control, it is possible to diagnose problems as they arise, and also to minimize negative consequences [49].

Further, it is worth noting that it is necessary to carry out control in order to obtain information regarding the movement of foreign children around the country. To do this, it is necessary to create a unified database for these children. This will help ensure and realize their rights so that they can receive a decent school education.

In Russian schools, as noted, the presence of migrant children has a positive effect on other children and the level of educational activities. Such an environment helps strengthen relations between representatives of different nationalities and eliminate contradictions. Citizens arriving from other countries wait a very long time to receive citizenship, but the bureaucratic system is so strong that children do not go to school or kindergartens.

Rights and issues affecting children of foreigners are the expiration of the 90-day temporary registration period. “The possibility of extending the period of stay is not legally established for children. Children's rights are violated. Contradictions in legislation deprive children of foreigners who do not have legal status in the Russian Federation of the rights to education, healthcare and social support” [49].

The law guarantees the right to education, “irrespective of any conditions, and makes schooling compulsory. However, although the lack of registration at the place of residence is not formally a condition for children to be admitted to school, in fact this is often the case” [50].

By law, migrants who do not have a residence permit, if there is no residence permit, must leave the country within three months, it is for this reason that they are simply forced to leave the country and return again, and this cannot but affect the educational activities of their children. If a child is not registered, then he has illegal status, and not all school heads are in a hurry to enroll a child, because there is a fear of administrative liability. Another barrier for a child to get into school or kindergarten is the lack of medical insurance, the cost of which is more than thirty thousand rubles, which is generally difficult for migrants to afford, so many do not actively try to place their child in an educational institution.

School education in the country is compulsory, but preschool is not, so parents wait for years for their turn in kindergarten, but, as a rule, places are distributed in accordance with their status; migrants are served last and do not always receive a place for their child. There are privileged families in our country, and those who should receive benefits are in total different categories.

“Every child has the right to education, but if we approach it from the point of view of the law, it is established that rights are given to citizens who are legally in the territory of the Russian Federation. It turns out that the rights and responsibility for the actions of adults are shifted to children. This provision is inconsistent with the Convention on the Rights of the Child, according to which the State undertakes to ensure that all children, regardless of their status or the status of their parents, have the rights to education, health care and protection from discrimination. An international treaty, according to the Constitution of the Russian Federation, has priority over federal legislation” [50].

A child cannot be deprived of the opportunity to study. A school is a place where children not only learn, they receive education and experience, the school helps them adapt and integrate into society, this applies to migrant children. And since school is a social institution, migrants trust it most.

There is no absolutely accurate data regarding the number of migrant children in the country; this also applies to the question of the number of families who do not have citizenship, and how many children are left without education. These children grow up in an environment of lack of attention, no communication with friends, and a limited social circle. But the state does not do what is necessary for these children; they are not included in the educational environment. The education system has many shortcomings, bureaucratic obstacles, xenophobia - these are not all the factors that influence the fact that not all children are enrolled in schools.

According to Rosstat statistics, in 2021, 61.3 thousand children under the age of 15, or 10.8% of arrivals, entered Russia from abroad.

“The net migration increase of children amounted to 21.9 thousand people, or 17.5% of the total increase, that is, these are children from families staying for long periods or forever” [51].

In addition, the number of citizens who arrived in Russia are minor children, their status is illegal, but the data on how many there are is incomplete. Accurate information is not published in any sources.

At least 10% of foreigners who come to Russia to work take their children with them. Considering that as of August 1, 2021, there were about 11 million temporary migrants in the country, theoretically there could be about a million minor foreigners in Russia [51].

Migrant families are a positive phenomenon and indicate that the country where foreigners come is an economically comfortable environment for them. In addition, children of migrants can become a source that will help increase the country's birth rate, and high mortality rates can be reduced.

Data on how many migrant children study in Russian schools is sketchy. According to Komsomolskaya Pravda, in the 2018–2019 academic year, about 60 thousand migrant children studied in Moscow schools (or 6.1% of the total number of schoolchildren in the capital). Similar figures were announced by experts from the Higher School of Economics, with the clarification that the figure includes internal migrants [52].

Several years ago, the Moskovsky Komsomolets newspaper published material that “in some Moscow schools the share of foreign students reaches 60%. Candidate for governor of St. Petersburg Vladimir Bortko said during a televised debate in 2021: “In a school in a residential area, 70% are children of migrants who do not speak Russian, but they are obliged to accept them” [53].

Meanwhile, chronic social isolation and discrimination against minorities, and their lack of opportunities to receive a decent education and subsequent successful employment, were cited as the reasons for the Paris events of 2005. That is, judging by the experience of France, Russia has a better chance of “getting Paris” if the situation with the adaptation of migrants and ensuring they receive an education is not resolved.

In 2014, State Duma deputies proposed obliging the Federal Migration Service to collect statistics on migrant children in order to ensure their education. However, the bill was rejected. Although the average working week of migrants reaches 59 hours with the norm being 40 hours, as a rule, their children, with rare exceptions, do not go to kindergarten; 44% of migrants’ children do not go to kindergarten, 14.9% do not go to school , according to the results of a survey by the Center for Migration Research conducted in Moscow in 2017 [54].

Many children in the capital go to school, but it turns out that they have not gone to school for two and three years, they have very bad behavior, they do not know Russian well, their knowledge differs from the knowledge of Moscow children, this is due to the fact that children studied in different programs.

In order to get a more complete and reliable picture of the problems of the situation of migrant children in Russian schools, as well as the attitude of non-migrant children towards them, a survey was conducted among respondents of two groups - children of migrants and non-migrants.

The survey was conducted in schools in Moscow and the Moscow region.

The average duration of residence of respondents (children from immigrant families) in Moscow was 4.23 years, and in the territory of the Russian Federation - 5.27 years. In this case, the line “in Russia” should be interpreted primarily as the time of residence on the territory of the Russian Federation, but not yet in Moscow. Accordingly, the average duration of residence in the city of Moscow is 19.28 years (at the same time, the share of those “born here” is growing, currently it is, as a rule, about 1/4 of the total sample; these are young people aged 18 years or older and older—usually adult respondents are surveyed).

The “negativity” of mono-foreign language is also obvious: the difficulty of communication, the limitations of mastering the culture of the titular nation, adequately entering into the life processes of the territory in full (hiring, promotion, mixed marriages, etc.).

In this sense, well-mastered bilingualism potentially provides some instrumental priority to its owners over “monolinguals” - just as in the modern civilized world, an almost mandatory condition for success is fluency in at least two or more languages (colloquial English plus national, plus other European, Japanese and etc.). If we take into account the duration of residence in Moscow (and the Russian Federation), as well as the average age of the children surveyed (11.34 years, ranging from 6 to 17 years), we can say that the preservation of the national language is very stable, strong, full-fledged adaptation is a slow process, possibly requiring a change of generations.

The survey we conducted allowed us to identify the following problems at school among migrant children:

− Insufficient knowledge of the Russian language.

− Educational results are low, which is caused by poor preparation of children.

− In some individual subjects there is either poor knowledge of the material or lack thereof.

− In order to encourage migrant children, additional classes are needed.

− Due to poor knowledge of the Russian language, there are problems with parents.

− Parents do not participate in the educational process.

− Children of migrants do not know local customs and generally accepted norms of behavior.

− Bad behavior in class.

− Absence from classes.

− Conflicts with other children in the class.

− Problems of legal status.

Also, parents themselves should help in mastering the Russian language. It should become a second native language. To do this, mother and father need to speak it at home. It is important to listen to Russian songs, watch Russian films, programs, read Russian newspapers, magazines, books. This will make the learning process better. And adults will have a unique opportunity to hone their knowledge themselves.

We can say that these problems lead to misunderstanding or complete misunderstanding between children in the process of communication; accordingly, children of migrants experience manifestations of discrimination, classmates tease them for their poor knowledge of the Russian language and inability to communicate. Therefore, foreign-born children must undergo mandatory testing for all when entering school. Since there are language problems, they can be successfully solved with the help of an individual approach and free additional classes. Such guys should be under the control of the administration. As a result, it turns out that the adaptation of foreign-language students largely falls on the shoulders of teachers, who, of course, are closer to the children and try to facilitate the learning process. However, another problem arises - most teachers do not know how to teach their native language as a foreign language, because they received a standard philological education, which included teaching Russian as a native language. Their high-quality retraining will help resolve the issue of teachers’ competence in working with foreign-language children. Thus, heads of educational institutions must send teachers to advanced training courses; in addition, existing developments are not sufficiently informative. It is necessary to change the training system in universities where they receive pedagogical education. After all, even if the number of foreign-born children decreases, they cannot completely disappear from schools.

In order for problems to be minimized, it would be quite reasonable to eliminate misunderstandings between children in communication, there are acceptable ways.

Namely, optimization of such areas of adaptation and integration policy as the creation of the “Code of Neighborhood”.

In other words, this will help prepare the conditions for children to receive Russian citizenship.

Secondly, we need to pay attention to the formation of non-conflict behavior and “soft dissolution” of migrant children in the Russian cultural environment. Using the experience of other countries will help make education more accessible, which will increase motivation to learn. This can be achieved by introducing a simplified procedure for obtaining citizenship. This applies to children, first of all, if they have lived for more than three years in Russia and were educated in Russian schools.

It cannot be denied that there is xenophobia among teachers. This phenomenon must, of course, be fought, because insults based on ethnicity are unacceptable. It is necessary to strengthen responsibility for xenophobia and increase the importance of public legal awareness.

Thus, it is possible to create regulations for the behavior of teachers in school and in society, and they should be observed. These kinds of regulations, of course, are unofficial, but they are necessary, and in professional circles everyone must comply with them. Such regulations are widespread in a number of Western countries, for example, in Finland, among journalists.

And so, the legal framework of the Russian Federation provides the rights to education to foreign citizens, these are equal rights for everyone. Foreign citizens have equal rights with citizens of the Russian Federation to receive preschool, primary general, basic general and secondary general education. Foreign citizens and stateless persons are endowed with rights and responsibilities in the Russian Federation on an equal basis with Russian citizens. The law guarantees the right to education, regardless of any conditions, and makes schooling compulsory. In accordance with current legislation, those foreign children who have a residence permit or temporary residence permit in the Russian Federation, as well as children of highly qualified specialists, can study continuously at school.

Literature:

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Approved and proclaimed by the General Assembly of the United Nations on December 10, 1948. // International agreements and UN recommendations in the field of protecting human rights and combating crime. 1989, no. 1.

- Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of November 4, 1950. // NW RF. 1998 No. 20. Art. 2143.;NW RF, No. 2, Art. 163.

- On ratification of the Council of Europe Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data: Federal Law of December 19, 2005 No. 160-FZ // Collection of Legislation of the Russian Federation. 2005.No. 52, part 1, art. 5573.

- Constitution of the Russian Federation (adopted by popular vote on December 12, 1993) (taking into account amendments made by the Laws of the Russian Federation on amendments to the Constitution of the Russian Federation dated December 30, 2008 N 6-FKZ, dated December 30, 2008 N 7-FKZ, dated February 5, 2014 N 2-FKZ , dated July 21, 2014 N 11-FKZ) // Collection of Legislation of the Russian Federation, August 4, 2014, N 31, art. 4398.

- Federal Law of December 31, 2017 N 493-FZ “On Amendments to Articles 5 and 17 of the Federal Law “On the Legal Status of Foreign Citizens in the Russian Federation” // “Collection of Legislation of the Russian Federation”, 01/01/2018, N 1 (Part I), Art. 77

- Federal Law of December 29, 2012 N 273-FZ (as amended on March 1, 2020) “On Education in the Russian Federation” // “Collection of Legislation of the Russian Federation”, December 31, 2012, N 53 (Part 1), Art. 7598

- Decree of the President of the Russian Federation dated November 14, 2002 No. 1325 “On approval of the Regulations on the procedure for considering issues of citizenship of the Russian Federation” (as amended on August 4, 2016) // “Collection of Legislation of the Russian Federation,” November 18, 2002, No. 46, Art. 4571

- Decree of the President of the Russian Federation dated 12/01/2003 N 1417 (as amended on 07/25/2006) “On amendments to some Decrees of the President of the Russian Federation in connection with the improvement of public administration in the field of migration policy” // “Collection of Legislation of the Russian Federation”, 12/08/2003, N 49, art. 4755.

- Decree of the President of the Russian Federation dated 06/05/2012 N 776 (as amended on 01/01/2018) “On the Council under the President of the Russian Federation on Interethnic Relations” // “Collection of Legislation of the Russian Federation”, 06/11/2012, N 24, Art. 3135.

- Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation of January 22, 1997 N 53 “On approval of the Standard Regulations on the Center for Temporary Accommodation of Internally Displaced Persons” (with amendments and additions) (as amended on August 10, 2016) // Reference system “Garant”

- Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation of June 16, 1997 N 724 (as amended on August 10, 2016) “On the amount of a one-time cash benefit and the procedure for its payment to a person who has received a certificate of registration of an application for recognition as a forced migrant” // “Collection of Legislation of the Russian Federation”, 23.06. 1997, N 25, art. 2943

- Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation dated December 1, 2004 N 713 (as amended on August 10, 2016) “On the Procedure for providing assistance to persons who have received a certificate of registration of an application for recognition as forced migrants, and forced migrants in ensuring travel and transportation of luggage, as well as payment of appropriate compensation to low-income persons from among these citizens" // "Collection of Legislation of the Russian Federation", 12/13/2004, No. 50, Art. 5063

- Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation of December 29, 2008 N 1057 (as amended on April 28, 2016) “On approval of the Regulations on the interdepartmental integrated automated information system of federal executive authorities exercising control at checkpoints across the state border of the Russian Federation” // “Collection of Legislation of the Russian Federation” , 01/19/2009, N 3, art. 382.

- Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation dated December 29, 2016 N 1532 (as amended on April 7, 2018) “On approval of the state program of the Russian Federation “Implementation of state national policy” // “Collection of Legislation of the Russian Federation”, 01/09/2017, N 2 (Part I), art. . 361

- Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation of December 27, 2017 N 1668 “On amendments to the Regulations on the implementation of federal state control (supervision) in the field of migration” // “Collection of Legislation of the Russian Federation”, 01/01/2018, N 1 (Part II), Art. 395

- Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation of December 20, 2017 N 1592 “On the preparation of proposals to determine for the next year the permissible share of foreign workers employed by business entities carrying out certain types of economic activities on the territory of the Russian Federation, and the recognition as invalid of the Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation of November 15, 2006 . N 683″// “Collection of Legislation of the Russian Federation”, 12/25/2017, N 52 (Part I), Art. 8166

- Order of the Government of the Russian Federation dated November 21, 2007 N 1661-r “On the Concept of the Federal Target Program “Economic and Social Development of Indigenous Minorities of the North, Siberia and the Far East until 2015” // “Collection of Legislation of the Russian Federation”, November 26, 2007, N 48 ( Part II), Art. 6029

- Draft Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation “On approval of the state program of the Russian Federation “Implementation of state national policy” (as of 08/26/2016)//(prepared by the FADN of Russia)

- Abramov R. A. Directions for improving the organizational and legal activities of state and municipal authorities in the field of preventing extremism and xenophobia in the context of an emerging personality // Management in Russia and abroad, No. 1. - M: Finpress, 2015.

- Abramov R. A. Features of management within the EU // Advances in modern science. - Penza: Publishing House "Academy of Natural Sciences", 2014. No. 12–5.

- Avakyan S.A. Head of the Russian state and regional power structures: experience and problems of interaction // Constitutional and municipal law. 2021. N 11. pp. 40–47.

- Avramova E. M., Loginov D. M. (2016) New trends in the development of school education. According to the annual monitoring study of the Center for Economics of Continuing Education of the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration // Educational Issues / Educational Studies Moscow. No. 4. pp. 163–185. doi:10.17323/1814–9545–2016–4–163–185.

- Aleksandrov D. A., Baranova V. V., Ivanyushina V. A. (2012) Migrant children and parents in interaction with the Russian school // Issues of education / Educational Studies Moscow. No. 1. pp. 176–199. doi:10.17323/1814–9545–2012–1–176–199.

- Aleksandrov D. A., Ivanyushina V. A., Kazartseva E. V. (2015) Ethnic composition of schools and migration status of schoolchildren in Russia // Educational Studies / Educational Studies Moscow. No. 2. P.173–195. doi: 10.17323/1814–9545–2015–2–173–195

- Biktimirova Quality of life: theoretical approaches and measurement methods, Ekaterinburg, 2015.

- Barazgova E. S., Vandyshev M. N., Likhacheva L. S. Contradictions in the formation of sociocultural identity of children of cross-border migrants // News of the Ural State University. Ser. 2. Humanities. 2015. T. 72. No. 1. P. 229–240.

- Bocharova Z. S. Legal status of Russian refugees in France in the 1920–1930s // Russia and the modern world. 2021. No. 2. pp. 161–176.

- Vandyshev M. N. Territorial principle of placement of labor migrants in a big city // A. I. Tatarkin, A. I. Kuzmin (eds.) Dynamics and inertia of population reproduction and generation replacement in Russia and the CIS. T. 2. Demographic potential of regions of Russia and the CIS: growth dynamics and inertia of changes. Ekaterinburg: Institute of Economics, Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. 2021, pp. 331–337.

- 32. Vandyshev M. N., Veselkova N. V., Petrova L. E., Pryamikova L. E. Interaction of migrant children with the host community in the system of school and preschool education: review of research results // K. V. Kuzmin, L E. Petrova (ed.) Interaction of migrants and the host community in a large Russian city: collection. scientific Art. Ekaterinburg: Publishing house of the Ural State Pedagogical University. 2021.

- Varshaver E., Rocheva A., Ivanova N. The second generation of migrants in Russia aged 18–30 years: characteristics of structural integration // Social policy and sociology. 2017. T.16. No. 5. pp. 63–72.

- Vorobyova O. D. Migration processes of the population: issues of theory and state migration policy // Problems of legal regulation of migration processes on the territory of the Russian Federation / Analytical collection of the Federation Council of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation, 2003. No. 9 (202).

- Vorozhtsov E.V. Youth unrest in France: problems of immigration and education // Issues of education / Educational Studies Moscow. 2021. No. 2. P. 23–29.

- Gerasimova I.V. Adaptation and integration are the most important elements of the state migration policy of the Russian Federation // Bulletin of the University (GUM). 2021 No. 6.

- Efimov A.G., Katsan V.N. The influence of population migration on the regional labor market and features of state regulation of migration flows in modern Russia. — Kursk: KSTU — 2021.

- Ivakhnyuk I.V. Labor migrants and integration policy // Employment Service. - 2015. - No. 3.

- Ivakhnyuk I. V. Management of labor migration: in search of new approaches // International Runova T. G. Demography: Textbook. M.: MGIU, 2013.

- Ivakhnyuk I. Migration policy: contribution to the modernization of Russia // Bulletin of Moscow University. Series 6. Economics. - 2015. - No. 2.

- Kolosnitsyna M.G. International labor migration: theoretical foundations and regulation policy// Kolosnitsyna M.G., Suvorova I.K. //Lectures and methodological materials - Economic Journal of the Higher School of Economics. — 2013. No. 4.

- Lukyanova M.N. Problems of strategic management of municipalities / Ross. econ. University named after G. V. Plekhanov. - M.: Publishing house REU im. G. V. Plekhanova, 2013.

- Malyshev E. A. Public administration in the field of external labor migration: theory and practice: monograph. M.: Justitsinform, 2017.

- Ostapenko Yu. M. Labor Economics, textbook, 2nd edition, revised and expanded, Moscow, INFRA-M, 2015.

- Parfentseva O. A., Ivanova N. P. Determining the labor force needs of the Russian economy taking into account the prospects for the socio-economic development of territories // Bulletin of the IKBFU. I. Kant. — Kaliningrad: Baltic Federal University named after. I. Kant, 2011.- No. 3.

- Sandugey A. N. On the fundamental principles of strategic planning in the field of migration // Migration Law. 2021. N 1. P. 8–14.

- Khalevinskaya E. D. World economy and international economic relations: textbook. — 3rd ed., revised. and additional / E. D. Khalevinskaya. - M.: Master: Infra-M, 2013.

- Khalbaeva A. M. Political management of migration processes in modern Russia: experience, trends, risks: diss…. Ph.D. watered Sciences: 23.00.02. - M., 2015.

- Feldman P. Ya. Russian model of functional representation of interests: national political traditions and current state // Bulletin of the Russian Nation. 2014. No. 4.

- Yugov A. A. Unity and differentiation of public power: the system of separation of powers // Russian justice. 2021. N 9. pp. 5–8.

- Institute of Migration and Interethnic Relations. Official website Electronic resource. Access mode: https://www.migimo.ru/razdel/55/

- The Russian Academy of Sciences. Official site. Electronic resource. Access mode: https://www.ras.ru/scientificactivity/2013-2020plan.aspx

- Trade Union "Teacher" Official website. Electronic resource. Access mode: https://pedagog-prof.org/

- Federal State Statistics Service. Official site. Electronic resource. Access mode: https://www.gks.ru/

- TVNZ. Official site. Electronic resource. Access mode: https://www.spb.kp.ru/daily/26926.4/3973119/

- Moscow's comsomolets. Official site. Electronic resource. Access mode: https://www.mk.ru/social/2015/12/14/chislo-detey-migrantov-v-stolichnykh-shkolakh-dokhodit-do-60.html

- Center for Migration Studies. Official site. Electronic resource. Access mode: https://www.spbredcross.org/images/pr_grant/Sbornik-materialov.pdf

What to do with the influx of migrant children in Russian schools

close

100%

Depositphotos

Increasingly, parents, when choosing a school for their child, look at the national composition of its students - how many are there who are politically correct called children of migrants. Actually, they always look if we are talking about large cities. Moreover, often representatives of our titular nation (80% of the population of Russia) in layman’s terms, by children of migrants, also mean citizens of the Russian Federation from the southern republics. This is what we have come to. About the same as France, Britain and many other European countries. Globalization, you know, it’s all over the place.

In good old England, the average number of children in primary school whose first language is not English has doubled over the past couple of decades, reaching almost 20%. Today, in a number of areas of London, English is not the native language of 40-60% of schoolchildren.

The other day, the problem was discussed at a meeting of the Council on Interethnic Relations with the participation of Vladimir Putin, during which the president spoke about this very thing: they say that in the West, the share of migrant children in schools sometimes reaches such a level that local residents take children out of such schools.

But in Russia we cannot allow schools to appear staffed only by migrant children. “The number of migrant children in our schools should be such that this allows them not formally, but actually deeply adapted to the Russian language environment. But not only linguistically, but culturally in general, so that they can immerse themselves in the system of our Russian values,” Putin said.

And I completely agree with him on this issue. We can add one more thing: it’s finally and long overdue.

But at the same time, I do not envy those who will have to carry out the relevant instructions of the president and draw up guidelines for action. Because the problem is very advanced. As for parents who take their children out of schools because of the “wrong” national composition, we already have this phenomenon on a sufficient scale.

We may not yet have schools fully staffed by migrants, but if you look at the national composition of the first classes in a number of schools, for example, in the south-east of Moscow (our Kapotnya has caught up with London in this indicator and even confidently overtaken it), then the number there those whom native Muscovites consider “migrants” go well beyond 60-70%, reaching up to 90% in other classes. The associated problems are well known to all parents. These children, when entering school, often either do not speak Russian at all, or speak poorly and do not understand Russian well.

Accordingly, teachers need to spend more time explaining the material to them, which is why other students fall behind. They are far behind. Then, however, some of these “children of migrants,” genetically charged to “stay a foothold, stay, succeed,” sometimes succeed very well in the exact sciences, while the relaxed “natives” are dragged away by “humanities” that is useless in the current cynical life " Just like in American schools, say, the Chinese and Indians succeed in mathematics. However, such successful people are still a minority of their fellow countrymen everywhere. While the majority become involved in bullying on ethnic grounds, various kinds of conflicts and problems due to dysfunction in, as a rule, poor families, with which school teachers often have no contact at all, etc.

The teaching community has been discussing this problem for several years now, but a systemic solution suitable for the entire country has not been invented. How, for example, can we make sure that the proportion of “children of migrants” does not exceed a certain level in one school or another, and in each of its classes, which hinders their adaptation? The President, by the way, said during the meeting that he did not have a ready answer. But no one has it yet.

Introduce a quota system? Should migrant children be distributed evenly across all schools? What about linking the school to the place of registration? Transport children of migrants on special buses to where they are assigned according to the national quota? But what about the fact that our share of children of “Slavic nationality” in the number of births is becoming smaller and smaller due to the low birth rate of some nationalities and high of others, as well as the surge in migration, including illegal ones?

Last year, the number of births in our country decreased over the year by almost 50 thousand, amounting to 1.44 million. This is the minimum figure since 2002. After 2014, the number of births in Russia has generally been declining steadily, and no amount of maternal capital, alas, has turned the tide. People don’t give birth “for money”; demography is a much more complicated thing.

The number of deaths last year exceeded the number of births by one and a half times (2.13 million, of which at least 350 thousand are the so-called “excess mortality”, that is, exceeding the average level for five years; almost all of these people were killed by Covid). The birth rate in Russia (on average 1.5 children per woman, 1.34 in Moscow) is below the level of simple replacement of the population (2.1 - 2.2 people). This means that there will be more and more migrants over time. Or the country will die out. There will be no one to pump oil and gas, cut down forests, sow and reap, and maintain infrastructure.

And if it goes at this rate, then it is still unknown for whom quotas will have to be introduced. And if the number of quotas is less than the number of “children of migrants,” then what should we do?

Don't enroll them in school at all? Deport? We must be prepared to give answers to such questions. Many will turn out to be not entirely “politically correct.”

To begin with, our Ministry of Education does not know exactly (and no one knows) how many “children of migrants” there are in the country. According to the ministry itself, there are about 140 thousand of them studying in schools across the country. In Moscow - from 60 thousand. However, at the same meeting with Putin, the head of the department, admitting that many such children do not go to school at all (and often they simply refuse to enroll them there, for example, there is no registration), still did not name the exact number of such non-students. That is, the Russian authorities don’t even know how many migrant children we have and how many of them do not study anywhere! According to some estimates, at least 10% of migrant workers who come to our country to work take their children with them. Considering that before the start of the pandemic (RANEPA data), there were about 11 million temporary migrants in Russia, about a million children could come with them. It turns out that only every 8-10th person goes to school? Or does the Ministry of Education simply not have adequate statistics on this matter? A couple of years ago, the Center for Migration Research, having conducted its survey, found out that in Moscow alone, almost half of migrant children do not go to kindergarten (which would be a good place for that same adaptation), and about 15% do not go to school.

In France or America, say, children of illegal immigrants are required to go to school (and are required to be admitted there). Otherwise, they will simply take you away from the family by force of our cursed juvenile justice system. We do not have.

On the other hand, I wouldn’t even wish my enemy to have his children study in such “public” schools with “in large numbers” of children from poor countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Because no one is raised there except morons-losers-forever-in-life, criminals and drug addicts. The level of education there is monstrous.

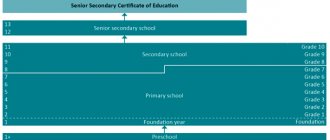

In a number of European countries with high levels of migration (the EU average number of first-generation immigrants is 10%, but this level is higher in a number of countries - in Cyprus 21%, in Austria, Belgium, Ireland and Sweden - 16%) schools organize “welcome classes” to help migrant strangers adapt. This is very rare in our country; most often these are purely commercial initiatives, for which already poor migrant parents must pay.

In theory, there should be at least mandatory - specifically state - Russian language courses, but they are rather the exception to the rule. That is, first the child must take a language course, and only then he should be assigned to a Russian school, and to the class that corresponds to his level of development.

But even in Moscow, such language courses cover only a few hundred migrant children out of tens of thousands. And in addition to language, there are also a lot of sociocultural problems that cannot be solved, say, by a simple ban (or, on the contrary, neglect of these details) for girls to wear, for example, a hijab at school, unless we are talking about those regions where it is simply formally prescribed or informally - yes, wear it.

But Europe itself is already faced with another unpleasant phenomenon: not only the first, but also subsequent generations of migrants do not integrate into the local society and do not even want to integrate. Take France, where the level of immigration is no higher than the European average, but the joke about renaming Notre Dame Cathedral into a mosque may soon become a reality. (There is no accounting of newborns by nationality; they are all French, if one of the parents is French. Although up to a third of newborns are born in families where at least one of the parents is an immigrant not from Europe).

In our country, where, I repeat, “natives of Slavic nationality” in everyday practice often confuse real migrants with visitors from the southern Russian regions, this problem of non-integration of Russian citizens into the culture of the “state-forming nation” is becoming more acute, but it is not even discussed for obvious political reasons.

In some regions, they are going to create separate classes for migrants. However, if we take into account that for full adaptation, especially in the Russian-speaking cultural and everyday environment, such children need from one to three or four years, then such classes sometimes only slow down this adaptation. They also create the ground for a kind of “racial segregation,” like any artificial division based on nationality. On the other hand, what to do if a boy/girl simply does not understand what the teacher is saying, and no one will pay him extra from the state budget for persistent additional classes with such lagging behind (and these classes, as a rule, are not available). Plus, their language of communication at home is not Russian at all. How much was said at one time about a mandatory Russian exam for everyone who enters the country even for temporary work! But what we have now is a complete profanation.

In general, if in the very next few years some large-scale and rather radical measures are not taken to adapt, and, if you like, to assimilate the ever-incoming flows of migrants and their children into the country, then in a couple of decades it will be possible to simply relax. Because in national, cultural, religious, and political terms, Russia will simply cease to be what it is now. It, of course, will not be the first and not the last such country in history, the main creator of which has always been not so much technical progress, wars and revolutions, but demography and great migrations of peoples.

Education - a right or a duty?

“The problem is not that the children of immigrants do not want to study, but that they are not accepted into schools,” says teacher and human rights activist Svetlana Alekseevna Gannushkina. This is despite the fact that the right to education is guaranteed by the Constitution. In her opinion, the “filter” is the school registration form - only electronic, through a personal account. As a result, some children risk being left without school and without a general education in principle, and without this they have a greater chance of joining a criminal environment.

“On the other hand, if a migrant family is not interested in adapting and integrating children into the Russian environment and culture and does not seek to send them to school and teach them the language, they must be forced to do this. The Constitution speaks not only about the right to education, but also that it is compulsory,” recalls Svetlana Gannushkina.

Preparation for admission of a foreigner to a Russian university

If a foreign citizen is thinking about enrolling in one of the universities in Russia, then first of all he will have to choose a study program and the educational institution itself. After this, the algorithm of actions will be as follows:

- In accordance with the requirements of the university, it is necessary to find out your capabilities, that is, whether a foreigner can apply for a budget place, whether an agreement on cooperation in the field of education has been concluded between his country and the Russian Federation, etc.

- After this, you will need to start collecting the necessary documents, some of which will need to be properly certified;

- Submit an application to the university;

- Complete the competition;

- Wait for the results of enrollment and, in case of a positive decision, move to Russia.

It is much more difficult for foreign citizens to enroll in a Russian university than for Russians, so if problems arise, foreigners can contact the university admissions committee, or employees of the Russian embassies or consulates in their country.

Children of migrants: quota or adaptation

In Russia, they started talking about the problem of teaching children in schools who speak Russian poorly. The government fears that Russian schools, especially in big cities, may face the same problem as Western ones. In Europe and the United States, there are schools filled almost 100% with migrant children, President Vladimir Putin said. As a result, local residents are forced to transfer their children from such institutions, and the migrants themselves, being in the majority, are less able to integrate into the linguistic and cultural environment of the country they came to.

In Russia, according to Putin, there should not be such schools in which the majority of students are migrants. Their number should be such that it will allow teachers not formally, but actually adapt them to the Russian language, culture and values, the president believes.

2175 “Dad said your parents are newcomers”

The Ministry of Education has already responded to this statement. As the head of the department, Sergei Kravtsov, said, the ministry is already preparing a system for assessing the educational needs of migrant children, which should be operational at the beginning of the next school year, although so far only in pilot mode. According to Kravtsov, the system will identify how well these children speak Russian and whether they can cope with the general education program, in order to subsequently build a suitable educational trajectory and psychological and pedagogical support programs for them. The department has also developed courses and manuals on working with migrant children for teachers and class teachers.

Parliament took up the issue of limiting the number of migrants in schools. As Oleg Smolin, first deputy chairman of the State Duma Committee on Education and Science, told Rosbalt, “if research shows that such a problem really exists, and we actually have schools in which the majority of children are migrants, quotas may be possible. But provided that these children are offered an alternative - and they can be accepted into one of the neighboring schools.”

At the same time, the deputy noted that he does not know of schools in Russia that would mostly consist of children of migrants. “Another thing is that we have quite a lot of schools filled mainly with children for whom Russian is not their native language. But most of them are Russian citizens,” Smolin noted.

According to the deputy, it is really not very good for immersion in culture when the majority of migrants are in school. “But if these migrants are legal, then children should receive the right to education. As for quantitative regulation, I think the simplest option is to distribute visiting children between nearby schools so that there are no distortions,” the deputy emphasized.

In addition, for those who have a poor command of the Russian language, it is necessary to organize additional classes to master it, Smolin believes.

The Teacher trade union also believes that there is no mass problem with migrant children in our country. “It exists for large cities, but also to a certain extent,” believes Olga Miryasova, organizing secretary of the Teacher trade union.

1069

Legacy of Corona: telecommuting is our future?

The main difficulty that teachers face in working with such students is their low level of Russian language proficiency. “If there are two or three non-Russian-speaking children in a class, most often this is not a problem. Especially when we are talking about elementary school. Kids learn everything quickly. Problems arise with older children who come to Russia and do not know the language. Such children cannot immediately get involved in the secondary school program. The low cultural level of parents and poverty do not allow them to help their child with homework or hire a tutor. If we allocated additional funding for special adaptive classes for children who do not speak Russian as a native language, teachers would welcome it. However, now there is practically no such thing anywhere. Most often, teachers are not paid for additional lessons with such children. The school itself can allocate money for this, but the poorer the region, the more difficult it is to do this. In general, it is the teacher’s task to teach any child. But, of course, they do this to the best of their ability, since along with migrant children there may now be children with disabilities who also need a special approach. We constantly talk about the fact that we have very large classes - sometimes 35 people. In such classes, there is less opportunity to give someone individual attention,” Miryasova said.

As Svetlana Gannushkina, chairman of the Civic Assistance Committee (recognized as a foreign agent in the Russian Federation), told Rosbalt, in American schools, children who come with no knowledge of the language are taught English as a foreign language. That is: in all subjects, children of migrants study together with others, but their English lessons take place separately. As a result, after six months they become comfortable and can move on to the group learning English as a native language.

“We should also have classes in Russian as a foreign language,” says Gannushkina. However, according to Smolin, such an issue has not even been raised in the State Duma and there are no plans to consider it in the near future.

“Now, unfortunately, the biggest problem is to get migrant children into school at all. We have the 43rd article of the Constitution, which categorically requires that all children study (this is not only their right, but also the duty of the educational authorities - this right to ensure). But in violation of the Constitution, migrant children are denied admission to school. This needs to stop. Where and how many of them there should be is the second question. Our percentage of migrants is much lower than in other countries, which, by the way, cope with this very well. Perhaps we just need to distribute them evenly among schools,” says Gannushkina.

“It seems to me that the spread of our culture is the best spread of Russian influence. We are interested in these children learning and appreciating our language and culture, perhaps even more than these same children, who, in the end, may go to a place where they will be more welcome,” she concluded.

Anna Semenets