Material? Not at all. In this sense, we, residents of megacities, are happier than others (although, of course, happiness does not come from money). Salaries allow you to look at the world with more confident eyes, stand stronger on your feet, and delight yourself with some pleasant little things.

The Lifehacker Telegram channel contains only the best texts about technology, relationships, sports, cinema and much more. Subscribe!

Our Pinterest contains only the best texts about relationships, sports, cinema, health and much more. Subscribe!

But man does not live by bread alone.

Unfortunately, living in Russia, I cannot buy what I want for any money.

This is exactly what we need to talk about.

Safety

She's gone. The police were renamed the police, the military were promised large salaries, all security forces were dressed in brand new uniforms. Did this have an effect? No, if you still want to cross to the other side of the street when you see a policeman. Not if wives instruct their husbands on payday how to avoid being robbed by the police.

Not if the driver keeps several hundred-dollar bills in his passport in case of a sudden bribe to the inspector. Not if a man in uniform walks into a supermarket and shoots people.

Do you believe the police? Me not. Moreover, we have long since moved away from the stage of “the police do nothing, so they are of no use” and have ascended to a new stage of “the police do a lot of things, so they should be feared.”

The attractiveness of Turkey

Statistics on emigration from Russia in 2021 indicate the growing attractiveness of Turkey. A simple procedure for obtaining a residence permit makes the country accessible to different categories of citizens:

- persons who have real estate in Turkey;

- entrepreneurs who want to start their own business;

- scientists engaged in research work in the country;

- students included in the mutual exchange program;

- persons arriving for treatment or on a tourist package.

Emigration statistics to Turkey are not tracked by official departments. However, according to unofficial data, about 500 thousand Russians live in the country. Some of the emigrants settled in Antalya. Türkiye is attractive due to its economic stability and social guarantees.

Health

I have health insurance and have money for things that are not included in this insurance, for example, dentistry. However, in order to go to the doctor, I need to consult with friends and acquaintances for a long time, so as not to end up with a non-specialist.

I still remember with horror one Moscow clinic where “doctors” work who do not have the right to practice medicine. And no one is even thinking about closing the clinic!

A dentist once found caries in my implant.

Against the backdrop of all this, the medicines and recipes are simply fantastic. A pediatrician who prescribes homeopathic medicines to all children. Ministry of Health promoting medicines whose effectiveness has not been confirmed by any research. Finally, there are numerous multidisciplinary clinics that are springing up throughout the country like mushrooms after rain.

Finding a good specialist is not only difficult, but sometimes almost unattainable. Not to mention all the subtleties that are cleverly spelled out in the insurance policy. This is included in the insurance, but this is paid for. For some reason, more than half of our possible services are paid.

Finding a job abroad without knowing the language is unrealistic

The most common misconception that stops you on the path to immigration is where and how to work. Everything is actually much simpler. The world is full of countries in which you can work, live and, moreover, know the language at a minimum level. For example, in Canada and Germany, knowledge of the Russian language will be a plus. And all because often immigrant families from the CIS countries deliberately look for Russian-speaking au pairs, caregivers or nannies.

You just need to start somewhere, over time the language will improve and other proposals will be found. New acquaintances and prospects will appear.

Unprofessionalism

This follows directly from the previous paragraph. We have entered an era of unprofessionalism in all areas, from medicine to laundries. People have forgotten how to write business letters. Asking to read text on the screen causes panic.

The following example will be understood not only by IT specialists, but also by simply people who know English. A system administrator at one of the Moscow airports (with honors from one of the most famous Moscow technical universities) proved to my friend, also an admin, that there is a difference between static routing and static routing.

The next time you complain about a flight delay at the airport, remember what kind of specialists work there.

And this is just one example, in one of the areas.

Low quality of all products

Exactly everything, I was not mistaken, from yogurt to cars. There is a lot that can be said about the Russian auto industry, but we will limit ourselves to what has already been said. In general, our auto industry is not the best. And if we talk about food, about clothes, then it’s just a song.

I live in St. Petersburg, Finland is nearby, and lately one-day tours of Finnish shops have become very popular.

At first I didn’t understand what the salt was, but then it became clear. We have two identical shampoos, the same brand. One was made in Russia, the second in Finland. Day and night. In the first case - thin water. In the second, there really is a shampoo that makes the hair “silky and shiny.”

Meat, fish, milk, no comparison. Why is that? I don't know. I don't understand why tiny Finland supplies our country with dairy products. I don’t understand why tiny Israel supplies huge Russia with radishes and strawberries.

The prices are amazing too. The same product costs differently here and in Finland. Or take T-shirts. Good American mountain t-shirts. In the USA - 16-20 dollars. In the Russian online store 50-60. In a real store there are 100. How do you understand this? And it’s like that in everything.

Emigration from Russia according to foreign statistics

Mikhail Denisenko

The plot of this article was repeatedly discussed by the author with colleagues from the UN Population Division as part of work on the topic “International migration in countries with economies in transition.” See United Nations, Population Division, International migration from countries with economies in transition 1980-2000. Diskette Documentation. ESA/P/WP.166. 8=may 2001.

- Emigration of Russians to non-CIS countries according to Russian data

- Emigration of Russians to non-CIS countries according to data from receiving countries

- Germany is the main country of departure

- The special role of Russia for Israel

- In Canada, Russian immigration is still insignificant

- The peak of emigration to the United States passed a century ago

- Immigration from Russia to Finland

| Ilya Repin Didn't wait |

Emigration of Russians to non-CIS countries according to Russian data

When studying the history of Russian international migration, researchers often rely on foreign statistical sources. Thus, on their basis, estimates were made of the volume of emigration flow from the Russian Empire to North America, white emigration during the civil war and revolution, and emigration of Soviet citizens to the West after World War II. Foreign sources sometimes turn out to be no less, and sometimes even more significant, compared to national ones. Apparently, they should not be neglected when studying the current emigration of Russians. Official statistical data from those states where emigrants from Russia enter can undoubtedly add to our knowledge about the not always transparent and difficult to account for emigration process.

Since the late 1980s, after the opening of the state borders of the USSR, migration ties between the former Soviet republics and other states have expanded significantly. In particular, the number of emigrants from Russia in 1990 was more than 36 times higher than the number of emigrants in 1986. In subsequent years, the emigration flow from the country stabilized at 100¦ 15 thousand people (see Fig. 1 and Table 1). In total, in 1989-1999, according to Russian data, 1,046 thousand people left the country for permanent residence abroad.

Figure 1. Emigration from Russia in 1980-1999

(according to the Ministry of Internal Affairs)

Table 1. Emigration from the Russian Federation to Germany, Israel, Canada, the USA and Finland

(according to the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs, people)

| Countries | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 |

| Total | 103694 | 88347 | 103117 | 113913 | 105369 | 110313 | 96665 | 84823 | 83674 | 108263 |

| Including | ||||||||||

| Germany | 33754 | 33705 | 62697 | 72991 | 69538 | 79569 | 64420 | 52140 | 49186 | 52832 |

| Israel | 61023 | 38744 | 21975 | 20404 | 16951 | 15198 | 14298 | 14433 | 16880 | 36317 |

| Canada | 179 | 164 | 292 | 661 | 874 | 754 | 1 003 | 1 300 | 1440 | 1837 |

| USA | 2322 | 11017 | 13200 | 14890 | 13766 | 10659 | 12304 | 12466 | 10753 | 11078 |

| Finland | 450 | 583 | 451 | 536 | 586 | 603 | 728 | 755 | 798 | 1068 |

Source: Demographic Yearbook of Russia 1999. M., 2000.

In the “Demographic Yearbook of Russia” and other official publications, information on migration between the Russian Federation and countries outside the CIS and the Baltics is provided according to data from the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs. The number of emigrants, or those who left Russia, is defined as the number of persons (including foreigners and stateless persons permanently residing in Russia) who have received permission to leave the country for permanent residence abroad. In published materials for 1987-1999, those who subsequently refused to leave are excluded from those receiving permission to leave.

It should also be taken into account that the Russian definition of international migration covers only that part of long-term international movements that is associated with a change of permanent residence. Simply put, the number of emigrants or immigrants includes those who declare that they are leaving Russia forever or coming to Russia. A Russian citizen who travels under a contract to work or study in foreign countries for a period of more than 1 year, as a rule, is not included in the number of emigrants recorded by Russian statistics.

In addition to the data of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, there are also estimates of emigration made by the State Statistics Committee of the Russian Federation. They are based on data on the deregistration of emigrants at their place of residence. Goskomstat's estimates of the emigration outflow turn out to be less than the estimates of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (in some years - by almost 25%).

Emigration of Russians to non-CIS countries according to data from receiving countries

According to Russian data, at the end of the 1990s, almost 97% of the emigration outflow from Russia went to 5 countries: Germany, Israel, Canada, the USA and Finland. Using data from the current accounting of international migration of these countries, comparing them with Russian data, we can try to correct the estimate of the number of those emigrants from the Russian Federation who went abroad for permanent residence (permanent residence) or, at least, for a long period.

It is clear that emigrants from Russia are considered as immigrants in other countries. In Germany, Canada, the USA and Finland, registration of immigrants from the Russian Federation began immediately after the collapse of the USSR - in 1992. In Israeli statistical publications, the distribution of immigrants from the USSR among the former Soviet republics begins in 1990.

In the immigration statistics of Germany, Israel, Canada, the USA, Finland and other Western countries, there is a group of immigrants from the former USSR who indicate the USSR, and not some former Soviet republic, as their last place of residence or place of birth. The share of such undistributed migrants was especially significant in the first half of the 1990s, and then, as the quality of registration improved and the composition of migrants changed, it gradually decreased. Thus, in Canadian data for 1992, the share of immigrants not distributed among the union republics was 82% of the total number of immigrants from the USSR, and in 1998 it was only 12%. This circumstance prompts the comparative analysis of statistical data to use not only explicit estimates of Russian immigration from national statistical publications, but also adjusted estimates taking into account undistributed immigrants from the former USSR (). Both explicit and adjusted foreign estimates of the number of immigrants from Russia to the corresponding countries are given in Table. 2.

Table 2. Immigrants from the Russian Federation

(according to statistics from Germany, Israel, Canada, the USA and Finland, people)

| Countries | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 |

| Germany | — | — | 84509 | 85451 | 103408 | 107377 | 83378 | 67178 | 58633 |

| — | — | 104616 | 106430 | 115930 | 117253 | 90807 | 74185 | 65241 | |

| Israel | 45522 | 47276 | 24786 | 23082 | 24612 | 15707 | 16488 | 15290 | — |

| 46351 | 47419 | 26911 | 25244 | 24858 | 16320 | 16727 | 15461 | — | |

| Canada | — | — | 151 | 832 | 1242 | 1724 | 2462 | 3729 | 4295 |

| — | — | 875 | 1343 | 1532 | 1983 | 2634 | 4258 | 4913 | |

| USA | — | — | 8857 | 12079 | 15249 | 14560 | 19668 | 16632 | 11529 |

| — | — | 9889 | 13772 | 17072 | 16562 | 20794 | 17656 | 14392 | |

| Finland | — | — | 2572 | 1735 | 1681 | 1844 | 2001 | 2386 | 2469 |

| — | — | 2670 | 1747 | 1697 | 1857 | 2007 | 2396 | 2469 |

Note: For each country: top line is the estimate based on published national data; the bottom line is the estimate obtained taking into account undistributed immigrants from the former USSR.

Table 3 presents a comparison of Russian estimates of emigration for permanent residence to Germany, Israel, Canada, the USA and Finland with estimates of immigration flows to these states from Russia made by the statistical services of these states. This comparison suggests that the emigration outflow from Russia was at least 1.2 times higher than that registered in Russia. Russian data diverge most strongly from Canadian and Finnish ones.

Table 3. Ratio of foreign estimates of the number of immigrants from Russia to Russian estimates of the number of emigrants to Germany, Israel, Canada, the USA and Finland

| Countries | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 |

| Germany | = | = | 1,35 | 1,17 | 1,49 | 1,35 | 1,29 | 1,29 | 1,19 |

| = | = | 1,67 | 1,46 | 1,67 | 1,47 | 1,41 | 1,42 | 1,33 | |

| Israel | 0,75 | 1,22 | 1,13 | 1,13 | 1,45 | 1,03 | 1,15 | 1,06 | = |

| 0,76 | 1,22 | 1,22 | 1,24 | 1,47 | 1,07 | 1,17 | 1,07 | = | |

| Canada | = | = | 0,52 | 1,26 | 1,42 | 2,29 | 2,45 | 2,87 | 2,98 |

| = | = | 3,00 | 2,03 | 1,75 | 2,63 | 2,63 | 3,28 | 3,41 | |

| USA | = | = | 0,67 | 0,81 | 1,11 | 1,37 | 1,60 | 1,33 | 1,07 |

| = | = | 0,75 | 0,92 | 1,24 | 1,55 | 1,69 | 1,42 | 1,34 | |

| Finland | = | = | 5,70 | 3,24 | 2,87 | 3,06 | 2,75 | 3,16 | 3,09 |

| = | = | 5,92 | 3,26 | 2,90 | 3,08 | 2,76 | 3,17 | 3,09 |

Note: The numbers in the table cells represent the corresponding ratios of the values in the cells of Table 2 to the values in the cells of Table 1.

Of course, foreign assessments cannot be considered impeccable either. But the uniform nature of the deviations of these estimates from Russian ones in all countries - their estimates are always higher than Russian ones - quite reliably indicates that the emigration outflow in Russia is underestimated.

The reasons for this underestimation require detailed study. Without this, the country cannot establish a system of reliable registration of immigration and emigration. The main one of these reasons, in our opinion, lies in the fact that today the importance of such a data source as recording exit permits has decreased. A person who is planning to leave for another country for several years or even for permanent residence can completely do without such permission. Many people simply don’t need it: it allows them to keep their housing in Russia, often their place of work or study, and ultimately protect themselves from possible risks associated with immigration.

Germany is the main country of departure

()

The topic of immigration is one of the most pressing for Germany, since, according to German statistics, as of January 1, 1998, there were 7.3 million foreigners in the country. Almost every 11th resident of Germany is a foreigner. The German government pursues an active migration policy and at the same time develops effective programs aimed at the economic and cultural adaptation of immigrants and especially their children.

Definitions of international migrants in Germany differ from those recommended by the UN. Foreign citizens are considered immigrants if they have received a residence permit and intend to stay in Germany for at least 3 months or more. Another category of immigrants are German citizens and people of German origin (Aussiedler), who return to their historical homeland and almost automatically become German citizens. It should be noted that the development of data on most socio-demographic characteristics of immigrants is carried out only according to Aussiedler. Emigrants include everyone who left Germany, regardless of their citizenship, for a period of 3 months or more.

Thus, comparisons between German and Russian data can be made based on some significant assumptions. German statistics include both short-term and long-term movements in their estimates of immigration flows. Because of this, in particular, the differences between Russian and German data reach significant values (Table 3). At the same time, immigration of people of German origin in Germany is considered as long-term migration. If we agree with this point of view, then at this point Russian data become comparable with German estimates. It can also be assumed that the migration balance reflects the amount of long-term migration to Germany, since those who came for a short period - less than one year - had to return to Russia.

Immigration from the Russian Federation and the former USSR plays a significant role in the life of modern Germany. According to German data, more than 2.2 million people arrived in Germany from the former Soviet republics in 1990-1998, which amounted to 21.5% of the total number of arrivals in the country during the specified period. More than 1.5 million immigrants were people of German origin, 675 thousand were foreigners. Immigrants from the former USSR come mainly from Kazakhstan and the Russian Federation. They account for 42.6% and 36.6%, respectively, of all arrivals to Germany from the former Soviet republics, 53.4% and 36.9% of Aussiedler arrivals, 21.7% and 36.1% of foreign immigrants.

Directly from Russia to Germany in the period from 1992 to 1998, from 590 thousand (according to published estimates) to 674 thousand people (including “immigrants from the former USSR”) arrived. Of these, persons of German origin ranged from 392 to 458 thousand, foreigners (primarily Russian citizens) - from 198 to 218 thousand people. The maximum influx of immigrants from Russia - more than 100 thousand people - was observed in 1994 and 1995 (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Immigration to Germany from Russia in 1992-1998

Note: Estimate is adjusted German data to include “migrants from the former USSR.”

According to Russian data, 450.5 thousand people emigrated to Germany between 1992 and 1998. The emigration outflow peaked in 1995. This year, the immigration influx of people of German origin to Germany reached its maximum value, according to both Russian and German data. According to Russian data, from 1993 to 1998, 243 thousand Germans left the country, which amounted to approximately half of the total emigration outflow to Germany. According to German data, this value was at least 331.8 thousand people, or 65% of the total number of immigrants.

According to German sources, the reverse emigration outflow to Russia during this period amounted to from 90 to 98 thousand people, of which about 16-18 thousand were Germans. Consequently, the balance of migration exchange between Germany and Russia was probably in the range of 500-570 thousand people in favor of Germany. We will take this value as an estimate of long-term immigration from Russia to Germany. With this hypothesis, the number of long-term immigrants, according to German estimates, was 1.1-1.25 times higher than the number of emigrants from Russia to Germany according to Russian data. A comparison of all immigrants from Russia recorded by German statistics with Russian estimates of emigration to Germany reveals a greater discrepancy between the data (Table 3).

The special role of Russia for Israel

()

In Israel, immigration is viewed not just as a vital process from the point of view of economic and demographic development, but also as one of the key elements of state ideology. It is therefore not surprising that the flow of immigration into the country is subject to careful statistical monitoring. In order to facilitate the accelerated and painless adaptation of immigrants in Israel, the Ministry of Immigrant Absorption was created. Control over immigration processes is based on a developed legislative framework, the basis of which is the Law of Return or the Law of Entry into the Country.

The definition of an international migrant in Israel's national statistics differs from that recommended by the UN. Citizens of other countries arriving or leaving Israel fill out special forms when crossing the border in accordance with the type of visa issued to them: immigration, tourist, temporary residence, etc. Information about persons with an immigration visa is then transferred to the population register. By definition, an immigrant in Israel is a citizen of another state who enters Israel for the purpose of permanent residence in accordance with the provisions of the Law of Return or the Law of Entry. In addition, Israel's international migration statistics highlight a specific category called “potential immigrants.” According to a circular from the Ministry of Interior, since 1991 this category includes persons who arrived in the country with an immigrant visa or certificate under the Law of Return with the intention of remaining in Israel for a period of up to 3 years in order to determine the conditions for settling as immigrants. Potential immigrants are included in the overall total number of immigrants for the year. In general, Israel has established a reliable record of immigrants with their various socio-demographic characteristics.

International migration for Israeli citizens is defined differently than for foreigners. The category of “departed Israelis” includes those Israeli citizens who intend to stay abroad for 365 days or more, but stayed in Israel for at least 90 days before leaving. The category of “returning Israeli citizens” includes those who have lived abroad for 365 days or more and intend to stay in Israel for at least 90 days.

During the period from 1919 to 1989, 270 thousand immigrants born in the territory of the former USSR arrived in Israel, or approximately 12% of the total number of immigrants during this period. From 1990 to 2000, Israel accepted more than 870 thousand natives of the former Soviet republics. This value represented 26% of the total number of 3,333 thousand registered immigrants who arrived in Israel from 1919 to 2000.

The distribution of migrants among the republics of the former Union as their previous place of residence in Israeli statistics has been given since 1990. During the period from 1990 to 1997, most immigrants came from Ukraine (more than 225 thousand), the Russian Federation (more than 220 thousand), Uzbekistan (about 70 thousand) and Belarus (more than 61 thousand). The percentage distribution of immigrants for the 1990s among their main areas of origin is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Distribution of immigrants to Israel by their main regions of origin

The definitions of emigrants in Russia and immigrants in Israel are generally identical, since the main criterion for their definition—leaving the country and entering the country for the purpose of permanent residence—is the same. In general, for 1990-1997, a balance was maintained between Russian data on emigration to Israel and Israeli data on immigration from Russia. According to Russian data, just over 203 thousand people left for Israel; according to Israeli data, about 215 thousand people arrived from Russia. However, in some years there are quite significant differences. Thus, in 1990, according to the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs, 61 thousand residents of the RSFSR received permission to travel to Israel. According to Israeli statistics, just over 45 thousand people from the Russian Federation arrived in the country (including potential immigrants). Probably, not all of those who received permission to leave Russia took advantage of it, and some of those who left went not to Israel, but to another country. In subsequent years, the differences between the statistical estimates of the two countries decreased, but at the same time there was a steady excess of Israeli estimates over Russian ones (Table 3). In 1995-1997, the difference between them was approximately 10%. With the utmost caution, let us assume that the probable flow of immigrants from Russia to Israel is 1.1 times greater than the emigration outflow noted in Russian statistical reference books.

In Canada, Russian immigration is still insignificant

()

In Canada, as in the United States, immigration processes have played and continue to play a key role in shaping the country's population. The country has a long tradition of recording and controlling immigration processes. In modern Canada, the legislative framework regulating international migration movements and the definition of the main categories of migrants are the Immigration Act of 1976 and the Immigration Rules of 1978. Control over migration processes is exercised by the Department of Citizenship and Immigration.

According to the definition adopted in Canada, immigrants are people who move to the country for the purpose of permanent residence (landing). This definition corresponds to the definition of emigrants adopted in Russia. It is on immigrants that our attention will be focused further. Canadian statistics also develop information on other types of international movements. Thus, long-term visitors include those people who arrived in Canada for a period of more than one year. Accordingly, short-term visitors include those who arrived in the country for a period of less than one year. The temporary foreign population occupies an important place in Canada's statistics. It includes those who arrived in the country of the maple leaf with permission to work or study, refugees and some other categories of people who arrived from abroad. As of June 1, 1999, Canada's temporary foreign population was 271 thousand people, of which 77 thousand were foreign workers and 87 thousand were foreign students.

In the 1990s, immigration from Russia was not as significant for Canada as it was for Israel, Germany, Finland, and even the United States. In 1992, the share of immigrants from the former USSR was only 1.3% of the 250 thousand immigration flow into the country. About 40% of immigrants that year came from Hong Kong, China, the Philippines and India. However, by 1998, the share of immigrants from the USSR increased and amounted to 6.3%. At the end of 1998, Russia ranked tenth among other states in the number of immigrants, overtaking Canada's long-time migration partner, Great Britain.

The volume of immigrants from Russia (Table 2) for the period from 1992 to 1998 can only be estimated approximately, since the share of immigrants not distributed among the former Soviet republics as their previous place of residence was 82% and 38% of the total in 1992 and 1993, respectively. number of immigrants from the USSR. In subsequent years, this value fluctuated between 6% and 18%. Taking these figures into account, we can assume that the probable estimate of the number of immigrants from Russia is in the range from 14.5 to 17.5 thousand people. According to Russian data, 6.3 thousand people went to Canada over the same time period.

Thus, the differences between Canadian and Russian data are quite significant; for individual years they are presented in Table 3. On average, in the second half of the 1990s, Canadian estimates were 2.6-3 times higher than Russian ones.

The peak of emigration to the United States passed a century ago

()

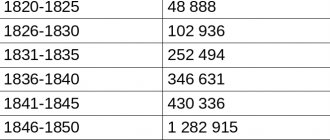

For many people around the world, the concepts of “wealth” and “immigration” are associated with the United States of America. From 1820, the year that continuous immigrant registration began, to 1998, 64.6 million people entered the United States. Immigration data is compiled by the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service, a division of the Department of Justice. The basis of immigration statistics is information on entry visas and forms of changes in immigration status. Immigrants to the United States are people who have been legally granted permanent residence in the United States. Basically, similar permission is obtained in other countries of the world. However, since 1989, it can also be obtained in the United States by changing the status of a non-immigrant temporarily staying in the United States to the status of a permanent resident of the country. The latter category of persons is also included in immigration statistics. In addition, according to the Refugee Act of 1980, refugees who have lived in the country for more than 1 year can also obtain permanent resident status. According to statistics, in 1992-1998, the number of newly arrived immigrants and immigrants who received this status in the United States itself were approximately equal. In 1989-1991, this ratio was sharply upset in favor of those who changed their status, since during these years more than 2.6 million illegal immigrants and agricultural workers legalized their position in the United States under the Reform and Control Act of 1986.

In the formation of the US population, immigrants from the Russian Empire played a significant role at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. From 1891 to 1920, 3 million people arrived in the United States from Russia. After a long period of calm in the late 1920s, immigration from the former USSR began to slowly pick up in the 1970s. Immigration to the United States increased markedly following the opening of borders and the collapse of the USSR. Moreover, in the mid-1990s, the former Soviet republics ranked second after Mexico in the annual number of immigrants. In total, there were more than 450 thousand immigrants from the former USSR in the United States during the period from 1990 to 1998, which is 5% of the total number of registered immigrants in the United States during this period.

In American statistical publications containing information on immigration, the most common characteristic of an immigrant's origin is not the country of previous residence, but the place of his birth. Comparing these data for the USSR for 1991-1998, one can see that the number of immigrants born in the former Soviet republics is 10% more than the number of immigrants who arrived from their territory. Thus, some immigrants - natives of the former USSR - arrived in the United States from other countries. The Russian Federation appears in American directories more often as the birthplace of immigrants. During 1992-1998, 98.7 thousand people who were born on the territory of the Russian Federation received immigrant status in the United States, and taking into account the adjustment for undistributed immigrants from the former USSR - about 110 thousand. The maximum number of immigrants occurred in 1996 (Table 2). At the same time, it should be noted that of those natives of the Russian Federation who received immigrant status after 1991, 53.5 thousand people arrived in the country before acquiring this status as refugees.

Comparing Russian and American data is a rather difficult task. First, in American statistics, an immigrant's place of origin is often determined by his place of birth, rather than by the country of his last place of residence. Taking into account the recommendations of international organizations and the specifics of Russian data, for comparison it is better to use those estimates where the origin of immigrants is determined by their last place of residence. However, it should be noted that at the end of the 1990s, the number of immigrants born in the Russian Federation was only 3% less than the number of immigrants who arrived from the Russian Federation. Secondly, in US statistics, estimates of migrants are given not for the calendar year, but for the fiscal year, which begins on October 1. Third, a significant portion of immigrants from Russia received immigrant status while already in the United States as a refugee or non-immigrant (), and most of them lived in the United States for one to three years or arrived there in the same fiscal year . Perhaps this circumstance explains the discrepancies between Russian and American data in favor of Russian data for 1992 and 1993 (Table 3). In 1996, the share of newly arrived immigrants was approximately 35% among all immigrants from Russia who received immigrant status, in 1998 - 55%. Fourth, unlike the American Immigration and Naturalization Service, Russian statistics provide virtually no information about who and how receives permission to travel to the United States.

Thus, when comparing data, one should take into account the difference between the calendar and fiscal year, as well as the fact that some migrants receive immigrant status with a time lag of 1-3 years. A comparison of the data shows that there are significant differences in the annual dynamics of immigrants between Russian and American estimates (see Table 3 and Fig. 4). The figure shows similar trends between American data for 1996-1998 and Russian data for 1993-1995, which may reflect the time lag with which Russians receive immigrant status.

Figure 4. Immigration to the United States from Russia

(according to the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs and the US Immigration and Naturalization Service)

The number of immigrants to the United States for 1996-1998 is 1.2-1.35 more than the number of emigrants from Russia according to Russian data. These estimates will help determine the likely magnitude of Russia's underreporting of emigration to the United States. Approximately the same estimates can be obtained if we compare annual Russian and American data for 1993-1998 (Table 3). However, given the wealth of American statistics, these conclusions should be clarified after a detailed study of them.

Immigration from Russia to Finland

()

Finland belongs to the category of states in which ideal, from a modern point of view, population registration has been established. The country has a regularly updated centralized population register, which can provide diverse and reliable information on migration movements. The definition of external migrants in Finland follows the definition proposed by the UN. Emigrants include Finnish citizens and foreigners leaving the country for more than a year. Immigrants include Finnish citizens returning to the country after staying abroad for more than 1 year, and foreigners coming to the country for more than 1 year.

Migration exchanges with the former Soviet republics, especially with the Russian Federation and Estonia, play a significant role in the functioning of the Finnish migration system. In 1992, more than 50% of the total number of immigrants to Finland came from the former USSR. By the end of the 1990s, this share had dropped to 30%, mainly due to a decrease in immigration inflow from Estonia. More than 20% of all immigrants come from the Russian Federation, and this share is quite stable. In total, about 15 thousand people arrived in Finland from Russia for the period from 1992 to 1998 for a period of more than 1 year, and about 1200 people left for Russia. The last figure is ten times different from those provided by the State Statistics Committee on immigration to Russia from Finland. Finnish estimates of the number of immigrants from Russia also differ significantly from Russian ones, according to which 4,457 people left for Finland from 1992 to 1998. Thus, over 7 years of migration, the population increase in Finland at the expense of Russia amounted to about 13,800 people.

It is curious that if we determine the origin of migrants not by the country of their last place of residence, but by their citizenship, then about 16 thousand Russian citizens arrived in Finland. This means that some Russian citizens arrived in Finland not from Russia. It should also be noted that if at the beginning of 1990 there were just over 4 thousand citizens of the former USSR registered in Finland, then at the end of 2000 the number of Russian citizens alone was 20.5 thousand.

To some extent, the differences between Finnish and Russian estimates of immigration are explained by differences in definitions. The Finnish definition of immigrants does not only include those who have arrived in the country for permanent residence. In terms of long-term migration in Russia, the total number of emigrants to Finland (adjusted for undercounting) is approximately 3 times higher than the registered emigration outflow.

Notes

. The probable (adjusted) number of immigrants is equal to the number of obvious immigrants from Russia plus the number of unassigned immigrants from the USSR, multiplied by Russia's share in the total number of obvious immigrants from all former Soviet republics. “Obvious” refers to those immigrants who are indicated in official statistical publications of Russia or other former republics. . The statistical basis of this section was made up of publications from different years: Statistiches Bundesamt, Bevolkerung und Erwerbstatigkeit, Fachserie1, Reihe, Gebiet und Bevolkerung. Metzler-Poeschel Stuttgart. . The publications of different years, Central Bureau of Statistics, Immigration to Israel, Jerusalem, and Central Bureau of Statistics, Statistical Abstract of Israel, Jerusalem, were used as source statistical materials for this section. . Statistical materials for this section are taken from the publication “Citizenship and Immigration Statistics, Ottawa; Facts and Figures. Statistical overview of the temporary resident and refugee claimant population”, Ottawa, for various years. . Statistical materials for this section were taken from publications of different years: US Immigration and Naturalization Service, Statistical Yearbook of the Immigration and Naturalization Service. US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC; US Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States. Among persons temporarily staying in the United States during the year, the proportion of Russians is insignificant. In 1996, it was equal to only 0.6% of all non-immigrants present in the United States. At the same time, almost 3/4 of all non-immigrants from the former USSR were Russians. . According to the Statistical Yearbook of Finland for various years.